Game On! Engaging IT Students at Kaplan U

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 06/19/13

Courtesy of Kaplan U |

The use of gaming techniques in higher education has been tested out aplenty in innovative environments such as MIT. But what about more traditional schools? Could the use of points, "missions," badges, and leaderboards really make a difference in more standard university environments, particularly one that was delivered entirely online? David DeHaven, dean of Kaplan University's School of Information Technology, set out in 2012 to examine how his school could exploit the fundamentals of gaming to enhance the experience of learning for its online students. He was monitoring the use of gaming theory or "gamification" in education to increase student engagement and motivation and thought it might have applicability to some of the challenges his own school was experiencing.

Starting at Go

One of the advantages of online programs is that a myriad of data points are available to show numerous aspects of a student's work and program engagement. DeHaven's department did an analysis of data pulled out of its course level assessment (CLA) system to understand what set students who were getting the best grades apart from those who were struggling. As he explains, "We were able to go in and pull the cross section of students getting really good grades and have the highest CLA scores and [look at] their behaviors. Where do they spend their time? What do they do?"

Then the department looked across the courses offered in its online IT program and found the one with the worst "U rate" -- unsuccessful rate -- across all sections, foretelling a high withdrawal or drop rate. That was a required class, Programming Fundamentals for Beginners. The department evaluated the course's structure, the material, and anything else about it that might influence a student's experience with the hope of uncovering what made it such a challenge to students.

At that point the faculty were brought into the conversation. After discussing gaming in general, DeHaven notes, "We said to them, 'If you could have your students do one or two things that would really change their experience, really demonstrate that they understand this material, what would they be?'"

The faculty really "stepped up and embraced it," he adds. "They came up with things I hadn't even thought of in terms of how badges could be applied and used to motivate and enhance the student experience."

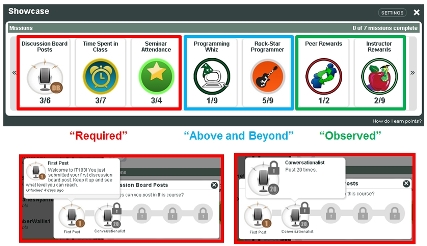

With all of that information and insight compiled, the department began to create a badging system. Akin to the physical badges issued to scouts, virtual badges designate that a person has demonstrated understanding, expertise, and completion of activities in a specific area and allow them to show that online.

The school went about creating a system whereby students could be awarded badges in three ways. The first was by instant response to behaviors favored by the department. "We automated as many of those as we could, because we could provide instant feedback to the student and give instant rewards," explains DeHaven. For instance, the system could automatically look at who was "in the classroom," the time they spent there, who posted first and how often. Based upon those metrics, the system could issue "early poster awards" or "multi poster awards."

Other badges were issued by the faculty themselves after the student had proven mastery by accomplishing "missions" or assignments. For example, explains DeHaven, one of the crucial behaviors might be to go out to a code library, such as Microsoft's CodePlex, an open source project hosting site, and pull out a particular routine or technique and demonstrate how to use it in programming. "That field trip, that going out and pulling a resource, synthesizing it, coming back, introducing it into the classroom, that's a whole set of behaviors and activities that once it's complete, can be looked at by the professor, who can say, 'Great job,' and assess a related badge."

A third category of badges was created to be issued by students to their peers "who have been particularly helpful on assignments or have done something that made something clear for them."

A leaderboard was ever present in the virtual classroom to show who had earned the highest number of points and attained the most badges.

Gaming Mechanics

DeHaven did an assessment of potential gaming platforms to handle the mechanics of keeping scores, issuing badges, and handling the leaderboard aspects. He'd used Badgeville at an event he'd attended, but after reviewing other offerings, he came back to it for a primary reason: They referred to themselves as a "behavioral platform," and that appealed to his psychologist background. "They didn't talk a lot about technology in the beginning. They didn't talk about integration. That came later. Their initial discussion was focused on what type of behaviors we were trying to incentivize or create." In the case of Kaplan that was improving student engagement and encouraging students to spend more time in the topic with their peers.

Integration of gaming required "deep" modifications in the pilot course, acknowledges DeHaven. Kaplan uses Pearson Education's eCollege for its learning management system. "You can't just take the basics and say, 'Oh, we're going to throw in some gaming techniques up there and see if this sticks,'" he warns.

Kaplan's internal innovation team took on the work of creating middleware to get Badgeville's badging system to work with Kaplan's LMS and CLA. That included asking faculty and students to go in and test out the leaderboard, the challenge assessments, and the badge set-up as part of the launch process.

The Clock is Running

On February 2, 2012, the initial gamification pilot kicked into gear in one section. The results looked positive almost immediately. "After the first week, the response we had from the students was really remarkable," recalls DeHaven. "I thought, it's new, it's the first week." Yet, the second and third weeks turned out to have even greater student participation.

For instance, it was typical for students to post to the discussion boards three or four times a week. "We had people posting 10 to 15 times," DeHaven notes. "They were coming back with comments like, 'I really like this recognition,' 'I like the personal competitions between us but also the collaboration we have,' 'It makes the class more enjoyable,' 'I wish we had these badges and this kind of recognition in all my classes.' Students were really receptive to it."

The results from that pilot were impressive. First, the students in the gaming section overall had roughly 10 percent higher grades than students in the non-gaming sections. They spent about 18 more hours in the classroom doing various activities than the non-gamers. They attended six more days in the term, showing up over and over in the online program.

Importantly, DeHaven declares, differences in demographics have shown no impact on the positive results. In other words, it doesn't matter what age, gender, or background the student has; gaming works.

On top of that the faculty went in and created "challenge assignments." According to DeHaven, "These assignments were harder. They were more complex. They required more time." Students received no point differentiation, such as extra credit, for taking the challenge assignment. However, they did earn related badges and it helped change their point standings in the leaderboard. Eighty-five percent of the students tackled those challenges, and the section still came out with higher grades.

A by-product of the effort was that faculty were able to look at the leaderboard and do a quick appraisal of which students had earned which badges and identify "some areas of opportunity."

Explains DeHaven, gaming "really empowers faculty outreach as well." An instructor could go back to a student "and say, 'You know what. I've noticed you've earned a lot of badges. But I've never seen you earn the early poster badge. You always seem to post later in the week. Is it your work schedule? How can we be supportive of your experience?'"

Beyond the Pilot

From that single session, the School of IT has rolled out the gaming format to multiple classes and sections, reaching about 700 students. On top of that other Kaplan programs, such as the School of Business, have also adopted gaming.

Later on, even when gaming techniques were added into other courses where the instructors weren't as involved in promoting the new features as the early adopter faculty were, "students self-discovered," says DeHaven, "and it drove positive results anyway."

However, this is just the first phase of the use of gaming at Kaplan. DeHaven calls it "motivational badging." Currently, there's no payoff outside of the individual class for earning the most points or gaining the most badges. In phase two that will probably change.

Phase two, he explains, will "hook into" competency-based learning. "We've started looking at our degree programs and classes and saying, 'What are the core competencies that an employer wants?'" The Department of IT is working with its advisory board, which has representation from Dell, Gartner, the US Department of Commerce, and other organizations, to provide feedback on what skills employees in IT need and how to assess that competency. In advance of getting their degree, Kaplan students will be able to pass the various assessments and earn a digital badge that can be added to their "digital backpacks" and posted to their profiles in LinkedIn.

For this work Kaplan is trying out open source leader Mozilla, which offers OpenBadges, an open standard for setting up a recognition system for digital badges. A digital backpack is a repository where a person can store badges earned and pull them out for display in public profiles.

What appeals to DeHaven about the OpenBadges approach is that it encourages participants to "expose" the methods for how a given badge was assessed.

For the assessments themselves, Kaplan will use PerformIT, an environment that replicates other environments, such as Linux or Windows, by which students can be tested with hands-on activities. Based on their performance there, possibly along with participation in a massive open online course delivered by Kaplan or some other institution, students could be awarded credit, says DeHaven.

The university recently rolled out its first PerformIT assessment related to Microsoft Office skills. For programs where Office proficiency is required, DeHaven notes, students "can actually place out of that course completely and move into an elective that's more appropriate for their skill level and interests."

Final Score: Gaming Wins Out

DeHaven's ambitions go even further for gaming techniques. He'd like to see how it could be used to drive involvement in the campus community and provide rewards, so that students could "start to recognize some of their peers who are experts and reach out to them, maybe get career advice and get help and create that collegial on-the-campus type of experience even though they're online."

As DeHaven declares, "Once you really enhance that student experience and give students new ways to engage, not just with the material but with one another, it's really amazing what you're able to accomplish."

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.