Attention Please! Getting Students to Tune In

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 11/20/13

When students enter one of Adam Wandt's night courses at the City University of New York John Jay College of Criminal Justice campus, the first thing they do is sit down and turn on their computing devices. They know that at precisely 6:15 pm they'll be able to access that evening's quiz for exactly 10 minutes. After that it's no longer available and they'll lose any credit they could have received for taking it. Once that period is over and the initial adrenalin rush has subsided, Wandt will continue popping up polls and other interactive activities that students are expected to participate in.

The goal: to keep these working adults and tired graduate students awake and engaged in the class after a long and tiring day of, well, life.

Wandt, an assistant professor in the Department of Public Management public administration program, hasn't always structured his courses this way. But over and over he was finding that even his best students were coming to class exhausted and ill prepared for a two-hour session on information security. Plus, they were continually distracted with their mobile devices.

The solution he eventually adopted turned out to be a software application that could be used in multiple other ways too. This was demonstrated by a group of CUNY faculty who undertook a research project to test the same program in their classes as a way to improve student performance.

Finding an Attention-grabber

Wandt, who serves as a deputy chair for the academic technology department of Public Management at John Jay, was convinced there had to be some form of technology that would allow him to reach students through their smartphones and tablets and encourage them to stay attentive to the topics he was instructing on.

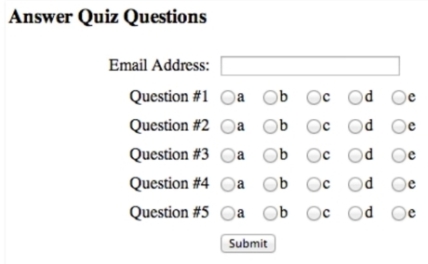

He discussed the problem with a doctoral student who also happened to be a software engineer; and on a lengthy bus ride shortly after that conversation, the student created a rudimentary version of what Wandt sought. A quiz built with PowerPoint slides would show up on the screen in class and the student would click a radio button in the software on their computing device to answer each question and fill in his or her email address for identification.

|

Source: CUNY

|

"It was very basic and it didn't do much; but I knew we were going in the right direction," says Wandt.

Shortly after, Wandt attended an education technology conference and happened to hit the tradeshows booths, where he discovered Via Response. This program, from a company of the same name, is a web-based tool that lets the instructor create quiz content that can be delivered to student devices for assessments, homework, surveying and polling, and social learning sessions. It integrates with Blackboard, Desire2Learn, and Instructure Canvas; it interoperates with other learning management systems via the IMS Global Learning Tools Interoperability specification.

Derrick Meer, president and co-founder of Via Response, told Wandt that he'd supply a free semester-long license of the software to any class of a faculty member who wanted to try it out. (While the program is always free to faculty, students pay at most $20 per semester for access; the price goes down for longer commitments.)

Wandt took that offer back to one of the academic technology sub-committees he participates in, the Academic Technology Research and Development Group. Skunkworks, as it's also known, pulls 40 active volunteer researchers from among almost every campus in CUNY to get together virtually and talk about academic technology. A handful of them -- representing LaGuardia Community College, The City College of New York, Lehman College, Queensborough Community College, and Queens College -- agreed to join Wandt at John Jay College in a research project during the spring 2013 semester to try the software with their students and report back on how it worked.

"We had professors in biology and chemistry and philosophy and public policy and cyber security all trying this stuff out in the same time," recalls Wandt. "We gave them the software; we set them free; and what we were really impressed to find out was that almost every researcher did something different."

Attendance and Polling

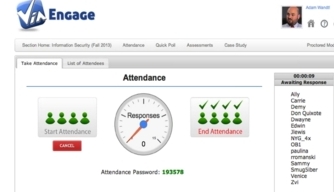

One instructor used the program simply to take attendance. At the beginning of class the faculty member would display an attendance slide with a password for the night, which the student had to be in class to see. They'd pick up their device, log into Via Response, enter the password, and be recorded as being in attendance.

|

Source:CUNY

|

Wandt tried a similar approach for the first couple of classes and found that it forced students to get to class on time so they'd see that password before it disappeared. But after a class or two, he eliminated that and replaced it with his quiz.

Wandt says he frequently hears complaints from undergraduate professors who "hate to take attendance because it takes too much time." But in some cases they're required to do so by law. "In this circumstance you could put [the attendance feature] on the screen, time it for 10 or 20 seconds, and then turn it off. Whether you allow students to register late or not is up to you."

Two other researchers -- including Wandt -- used Via Response as a classroom clicker. "The student doesn't have to go to the bookstore and spend $40 or $50 on [a dedicated device] they're never going to use again," he notes. "They use their smartphones or laptops or tablets." He would create "quick polls" in advance and use those to make sure the students understood the topic or to make sure they stayed on topic.

Homework and Tests

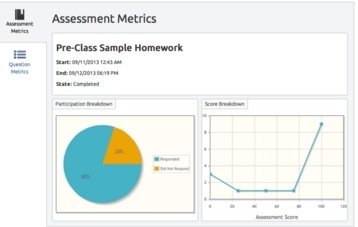

Other researchers in the project used the homework module of the program. The instructors would enter questions into a "curriculum content bank" and then assign a set of homework questions to the students. "Then they were able to monitor the homework module over the course of the week," Wandt explains. "If they saw students not taking the homework [or] having difficulty with the questions, they could reach out. If students did very well, they could congratulate them." Then, right before the course would begin, the teachers could check the general metrics to see where the majority of students had problems so they knew where to put their focus during the class.

|

Source: CUNY

|

"We don't want to waste class time going over ideas and topics that students are already proficient with. By using the homework module, professors were able to get a really good idea of where their students' strengths and weaknesses were before they came into the classroom, so they could focus on the right places," he adds.

Wandt expanded on his quiz practice by delivering full-length midterms and final exams through the software. But in those cases he also recommended that students bring in a laptop or use a college-supplied one. "It could be a little problematic taking a 50-question quiz on a smartphone," he notes. The outcome was a "wonderful, positive experience." The program allows for multiple choice, true-false, short answer, and long answer questions.

Magical Metrics

When the semester ended, Wandt surveyed the students in his class and those from another course. The emphasis for the questions was on usability and value.

The majority -- 69 percent -- found the program "intuitive" or "very intuitive." Most students were able to get the program going on their devices with little help. Three quarters were able to use it without any outside help. The others "needed somebody standing over their shoulder for a minute or two of help." But for the most part, he added, faculty and students "could get set up on day one."

To avoid delay in his courses now, Wandt asks his students to set up the software before class. He ensures it happens by giving them a homework assignment in the program. "I find that works really well," he says. "It gives the student time to play around with it before they come into the classroom."

The entire survey group "agreed" or "strongly agreed" that the use of Via Response by the faculty "forced" them to come better prepared for the class; 90 percent said it helped them succeed. "I think these are really the magical metrics," Wandt reports. "The reason I started this project was because as a professor I was getting very frustrated with my students not reading properly before class. I understand their stresses, that they're busy. But I also need to make sure when we all get into the classroom, we can have a very targeted conversation about something they already have a background on."

The use of a targeted software program showed that applying technology to encourage students to do their preparations could help them in small but influential ways to fulfill their learning objectives, Wandt observes. "If we can get over our preconceived notions about smartphones in class [being] bad, we can really give them tools that will help them succeed in the long run."

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.