Using Video Grading To Help Students Succeed

Creating videos to supplement the grading process can personalize the instructor-student relationship, clarify expectations and help keep learners on track.

Instructor grading videos meticulously document how the professor

arrived at a grade.

In my seven years at the helm of the fully online Master of Education program in Instructional Design & Technology at West Texas A&M University, I have never found an admissions tool that reliably separates good prospective students from those who will likely fail. Undergraduate GPA, entrance interviews, entrance essays, standardized test scores all have done an abysmal job of predicting success in my program. A student with a 2.3 undergraduate GPA is probably going to struggle and one with a 3.75 is highly likely to soar like an eagle, but for the Great Middle with their 2.65 to 3.25 GPAs, anything is possible — from All-Star status to immediately assuming fetal position in the face of our workload.

How do we work with this "high-risk pool" to maximize their chances of success? Setting crystal-clear expectations in the Program Handbook clearly helps. I have also been known to read the Riot Act to marginal prospects on the phone prior to saying "yes" to admission: "Fred, the success rate for people who have shown up on my doorstep with General Studies diplomas, 2.4 undergrad GPAs and fuzzy career goals has really stunk. If you are not going to join them on the scrap heap, here is exactly what I am going to expect from you from Day One…."

But beyond these obvious strategies, one invaluable technique that is rarely employed to help push students in the right direction is the use of instructor-created videos to supplement the grading process.

How It Works

The grades for all my courses are the average of the midterm project and the final project, provided the nongraded weekly class assignments have been submitted on time and are acceptable. The moment of truth is often the evaluation of the midterm project of the first technical course.

If a student's performance is so promising that I am convinced that written comments are all that is needed to elicit the next level of excellence, that is what he or she gets along with the letter grade. On those very rare occasions where performance is so horrific that it is immediately clear beyond a reasonable doubt that the student is not going to profit from continuing the program, I do not hesitate to counsel the student in the direction of the exit ramp.

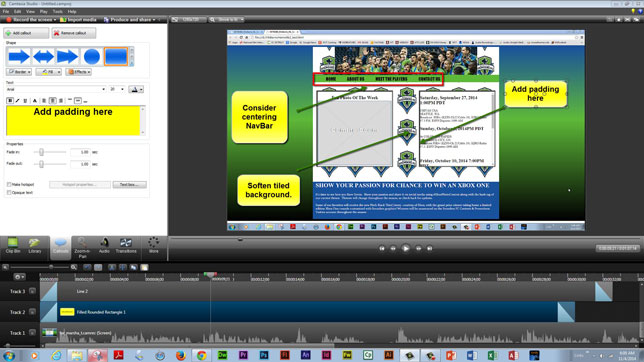

For those in between, I respond to their projects with an e-mail that provides access to a grading movie of some three to seven minutes, which I create with TechSmith's Camtasia software. The visual focus of this movie is the project they turned in, with me using Camtasia's wonderful toolset to zoom in on details and highlight issues. For example, I will often draw straight lines on students' Web page designs to show how the alignment of objects could be improved. The audio track features me giving them exactly the same critique of their work that they would receive if they were standing over my shoulder looking at the screen during a one-on-one visit.

3 Benefits of Project Evaluation Movies

Making it personal. My students often come from "bad academic homes." They have had some professors in the past who were more tied up with presenting at conferences and generating publications than with making a genuine connection with students. Students have too often seen e-mail notices informing them that Dr. Shmow will be traveling for the next five days on important business and will be responding to their e-mails sometime after she returns. They have had their papers rated by equally distracted graduate assistants, often with marginal English language skills and little understanding of the real concerns of the people behind the papers.

Granted, these students have become very goal-oriented about jumping through the necessary hoops to get a graduate degree, and have learned not to care about institutions that they believe don't care much about them. They may have even chosen a program that was online because they are not confident in their abilities, and they hope to slip more easily under the radar in the distance learning environment.

The first time such students get a personalized movie critiquing their work, they are dumbfounded by the realization that this particular professor is not just "talking the talk" of student engagement, but "walking the walk" as well. I have gotten post-critique e-mails that were close to tearful in gratitude, even when the list of items to be improved in their work was considerable. This can create an instant sea change in the student/teacher relationship, and a heart-level commitment not to let this guy down.

Demonstrating fairness and limiting grade appeals.Another aspect of those "bad academic homes" is that many marginal students have been the victims of some genuinely uncaring and sometimes unfair grading. No human activity is completely guided by rationality, and grading student work is certainly no exception. The widespread mythology that the now-omnipresent grading rubric eliminates or even seriously constrains the irrational component is nonsense, since rubrics themselves are often entirely open to interpretation. No honest instructor can deny the possibility that, despite his best intentions, the way he grades a project might be influenced by what kind of experience he had with the last person in his class named Terrence, Tammy, Taiko or Takeisha. The unconscious simply cannot be willed out of existence. Nor should we discount the effects of mood, weather, biorhythms or the quality of today's lunch on the grading process.

This very week, we had a brief computer network meltdown at my university, which resulted in me grading the same piece of student work twice without realizing it. The mature student was amused to get two grade explanation e-mails from me that week, one justifying the grade of A in careful detail and another doing exactly the same for the grade of B. On rereading both, I still think I was right both times! (She kept the A.) While high-quality students shrug off the occasional odd grading decision the way a batting champion refrains from arguing an occasional strike called by an umpire on a pitch out of the zone, marginal students can easily become obsessed with a sense of persecution by what they see as a pattern of unfair or incompetent grading that resonates with their past experiences.

Grading movies greatly reduce this problem in two ways. Because the video meticulously documents exactly how the professor arrived at the grade, the student is forced to drop any illusions of arbitrary or capricious treatment. More important, by forcing the grader to justify all his opinions about the work with visual evidence, the grading itself becomes more fair and reasonable. At least 20 percent of the time, I change the grade that I would have given a project during or after making a grading movie. I have learned not to start the movie by telling the students their grade, because I have had to go back and edit that part of the sound track too many times.

Removing all doubt about expectations.The projects that receive grades of C, D and F typically fall into two categories. There are a few students who know perfectly well that they are turning in garbage, but are hoping that I am too lazy or blissed out to inconvenience both of us with a bad grade. Maybe they think the real grading scale is A=Average, B=Below Average, C=Comatose and D=Dead. Or maybe they have had the experience of teaching assistants so terrified of retribution on the dreaded student evaluations that they are afraid to give any work a grade less than B, even if it is unfit to line the birdcage. I have also run into a few students who are convinced that their grades have little or nothing to do with their work, but are simply a measure of their success in relationship-building with their professor. In many of these instances, a grading movie that just sends the message "There is a new sheriff in town, and he really cares about the quality of your stuff" is all that is needed.

Most students are sincerely shocked when they get a poor grade on that first project. They have been accustomed to the subtle discrimination of low expectations and are "blindsided" by realistic ones. Often, they sincerely believe that if they have made a minimal pass at some of the items on the list of Required Project Specifications, they have done the job well and earned the best possible grade. Just yesterday, I graded a graduate midterm project which was a presentation manual created in Adobe InDesign, intended for teaching a technical topic in a community college. The student, whose native language was English and who holds a rather prestigious job with a local health maintenance organization, had 28 spelling and grammar errors in the first 5 1/2 pages of the work. This student clearly did not understand that written expression mattered in this project, even if the course goals were predominantly technical. She certainly understood it when she saw a large sample of those errors highlighted in the grading movie, and I know this realization will make a huge difference in her final project.

Theatrical directors report that some of our most respected dramatic actors are completely useless on the first reading of a script. Once the director clearly delivers an expectation, such as "Play this like you recognize the suspect you just arrested is the guy who robbed your lunch money on the playground when you were in second grade," they are magnificent on the stage or screen, and get it just right. Some students are like that, and video can be the ideal medium to make the necessary direction clear.

Creating Effective Grading Movies

As with any interpersonal interaction, the devil is in the details with grading movies. Here are some pointers to assure that your investment of time and energy pays off:

Manage expectations. Triage must guide you when deciding when to do a grading video. You don't do them when you know they are not needed, or when you know they are desperately needed but will not help. Make sure your students understand that they can expect a grading video only when you feel it is the most efficient method of communicating about a project and that sometimes you will not consider one necessary. If you use grading videos at all, any student should be able to request and receive one for any project where he or she desires more information about how the project was evaluated.

Continuing with the analogy of the movie director, you can't give the actor an explanatory note on every word on every line in the script. You need to be selective and concentrate on typical instances of the student's most persistent weaknesses and strengths. No grading video should exceed 10 minutes. Resist the temptation to reteach the course in the grading video.

Be realistic about production standards. You cannot afford to play the perfectionist with these movies. When I make an instructional video of one hour, I expect it to be viewed by hundreds of students over four to six semesters before it needs to be replaced. I don't mind investing 20 or 25 hours of effort in perfecting that video. A grading movie is only going to be viewed once or twice, and by only one student. Many grading videos will need to be produced in the tiny window of time between the due date of the project and the grading deadline. So good enough has to be good enough. There is no time to eliminate all the coughs, filler words and dead spaces through careful timeline editing. There is no time to ponder whether this turn of a phrase would be slightly better than that one, as you would if you were writing a journal article. I never do the produce-and-share step on an instructional video until I have watched every second of it with full attention at least three times. With grading movies, it is, of necessity, "one and done." The students will understand this even if they take my Computer Videography course covering the importance of production values.

Refer to touchstones. A grading video must demonstrate a strong connection between the quality criteria you stated in your project specifications document and how you evaluated the project that the student delivered. You don't want students to feel that the movie is only documenting your fleeting emotional reactions to their work. I often show parts of the actual project specifications or course syllabus documents in the grading movie itself, and highlight exactly the phrase that shows where the student needs to improve. Sometimes I find it valuable to shift the video to a component of a quality project done by another student to emphasize an example of a correct or imaginative use of a particular technique.

You always want to provide the student with guidance on how to make things right. Touchstone references are the perfect tool for this purpose. One recent student included a note saying that a required element was missing from his project because the book wasn't clear on how to do it and he "couldn't find any other resources about it." I used the grading movie to show how to access the "unavailable" information with four clicks from the Reference Guide for the software used in that project.

Never breach confidentiality by using a grading video of a poor student performance as a teaching tool for other students, even if the work you are critiquing has no identifying elements and the student who created it can be coerced into giving permission for this use. It is perfectly okay to use a very good performance as a teaching tool for others (with permission of the student), provided what you say in the movie is 75 percent positive.

Say good stuff too. Criticism should be directed at the project, not the student who created it. It should be tempered, to the very limits of honesty (but not beyond them), with warm recognition of what the student did well. I always try to start and end by saying something positive. I have gone to considerable trouble to try to find something to praise even in projects that I graded F. The message is never "You stink!" or "Your work reeks!" but "I see some places here that show promise and growth. Now let's look at what I will be expecting when you get to the next project." You don't want students to come away thinking that they are simply hopeless and cannot meet expectations through any effort on their part.

Keep your cool. The last question that I reflect on before I push the Send button on an e-mail containing a grading video is how I would feel if I were sitting in a grade appeal hearing with the department chair and the dean, and this student played my grading video on his laptop attached to speakers and a large screen. Would the video be judged as helpful and caring, or as demeaning, offensive, discriminatory and unskillful? Would it take the part of a good friend trying to point out the path to the best result, or sound like a petulant, petty official out of sorts because an "inferior" in the institutional chain has not shown the requisite respect for his just demands for compliance? If in doubt, throw it out. A career can be destroyed by a single moment of carelessness or stupidity, when you are the one documenting your bad day on film for posterity. So suggest, don't savage.

Grading Students as if Both You and They Were People

The advantages of fully online college courses have been well-documented. But their limitations are also getting increasing attention, and the biggest challenge is the chasm they can create between teacher and student. Distances of hundreds of miles can make it very difficult to know each other, to experience the class from each other's point of view and to respond appropriately to each other's needs. Used poorly, technology can be just one more instrument of our mutual alienation, for which our society has plenty of instruments already. Used wisely, through devices such as well-done project grading movies, that same technology can go a long way to bridging the distance between your unique humanity and the equally unique humanity of each of your students.

About the Author

Dr. Richard Rose is program director for Instructional Design and Technology at West Texas A&M University. He retired as a senior instructional designer at Boeing and Microsoft.