4 Rules for Writing a Better RFP

Issuing a request for proposal that gets the kind of response you want and need from vendors starts with refining your RFP process altogether.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 05/12/16

Lawrence Levy, president of Enrollment Rx, which sells cloud-based customer relationship management (CRM) for higher ed, sees a lot of RFPs come through his company. Those that cause him grief are the ones that form "two ends of bad on the spectrum." On one end of bad is the RFP with "1,500 questions in it and the same question is repeated 10 times," he explained. In that scenario, he imagines, the procurement person went to all of the committees involved in the technology purchase and said, "Give us all the questions you would ever want to ask in an RFP." But nobody has gone through and winnowed out the duplicates. "That's ineffective," he said. "It's certainly not a good use of our time to respond to something like that."

The "bad" on the other end of the spectrum is the RFP that's dozens of pages long, but the actual requirements only take up half a page. Rarely in that situation is the institution asking the "right questions," said Levy.

In both cases, the RFP appears to be the first step in an institution's process of discovery. "They'll issue an RFP that misses the mark," Levy sighed. "They're either copying and pasting other RFP templates they found that don't exactly fit their requirements, or they're putting out a phone book worth of questions — seeking a product that maybe doesn't even exist on Planet Earth." The result: bad decision-making.

Compare that to the process in place at Babson College (MA). Robyn Betts, senior IT leader and director for the Project Management Office (PMO), won't even put together a request for proposal until the entire project team has been pulled together with all the key stakeholders — "whether they like it or not," she said.

The team approach is important, she emphasized, "because everyone holds the key to different pieces of information. And if we don't know all of that when we're putting out an RFP, we're going to have major surprises at the end."

Once the group is in the room together and the governance structure is in place, the team members develop a project charter. This is a "pretty basic document," Betts said, "that outlines why you're doing the project, what the problems are that you're trying to solve, what the opportunities are that you're trying to introduce and what the success criteria are." The charter, she added, is "invaluable for really understanding what 'good' looks like at the end of this thing."

That's just the start of the work undertaken by the project team way before the Massachusetts institution finally issues an RFP.

As Betts succinctly explained, writing a better RFP is really about putting a process in place and understanding what you want out of it.

1) Do Your Homework

Even before the project team is formed for an IT product or service that meets a specific monetary threshold, an official request goes through the Babson PMO to have the proposed technology vetted by the "business owner and others around the college," said Betts, specifically to make sure that it "makes good business sense and adds value to Babson."

Just introducing that step alone was an improvement on what existed before: a motley collection of haphazard practices where a college director would create an RFP that might or might not provide much detail; or even worse, a school leader would meet somebody somewhere and simply sign a contract based on good feelings.

Under the more centralized process, the PMO assigns a project manager and, potentially, a business analyst to work with the college unit that needs the solution. That team develops a project charter.

Pre-RFP, the project team does discovery work that may include speaking with possible vendors ahead of time, conferring with Gartner and Educause, reading magazine articles and talking with colleagues at other schools to "really get a sense of the landscape." As Betts pointed out, "Truth be told, we're all reinventing the world, so there's plenty of information out there."

Once the project team and sponsors have signed off on the project charter, the RFP is crafted in two parts, said Betts. One is a "narrative" that includes a lot of the charter text: "Why are we doing this? What's the goal? What's the scope of what we're looking for?" The second part is a requirements matrix.

2) Develop the Matrix

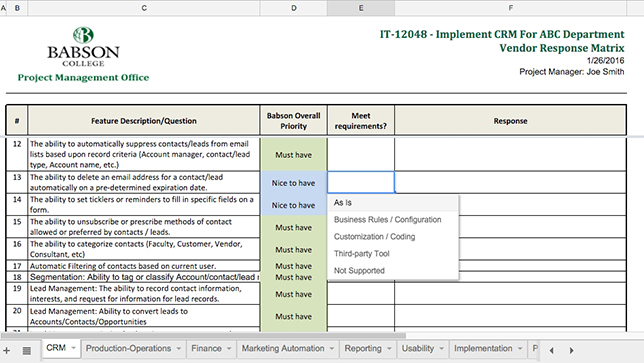

As the project team meets, it begins compiling a list of requirements for the technology acquisition that will be documented into a matrix — actually a spreadsheet with multiple tabs for grouping functional areas. A matrix could have somewhere in the ballpark of 200 requirements, said Betts. By dividing them among different functional areas and giving each area its own tab, however, "it's not as daunting" as it sounds.

"It also allows vendors to provide information in a more structured way. Perhaps they have different subject-matter experts who can comment on these things, so they can farm it out if they want to," Betts explained. "And for us it's great because, honestly, the value in all of this is getting our own ducks in a row before we go talk to people, to really make sure we know what we're asking for."

The items on that roster are prioritized through discussion and divvied up in two groupings: "need to have" and "want to have."

That matrix is provided with the RFP for vendor response. In the past the vendors were expected to answer yes or no to each item. Now, said Betts, Babson has gone more "robust" in its asking. The institution wants to know if the feature is "out-of-the-box functionality, custom development or something that's configurable."

At the same time, the vendor is asked to explain where there are requirements in the matrix that include third-party tools or additional software or any additional expense. That way, the college will know what level of effort is involved to meet the requirements. "'Yes' is a great answer. But if it means it costs more money or costs more time, that may be different than what we had agreed to," Betts said.

Babson College uses a matrix to prioritize technology requirements and identify features that might require additional cost or effort to implement.

3) Improve Processes

In the best of all possible worlds, buying a new technology provides an institution with the opportunity to rewire its business processes and integrate disparate systems for greater efficiency and impact. At Babson, parallel with the requirements gathering, the project team diagrams the relevant business processes and considers how those might be overhauled.

As Betts described, "How people do their business today is documented in graphical format and then how people would like to do their business tomorrow is documented as well, to show who's doing what at any given time." Going through that exercise "really helps to eliminate redundancies and make those lightbulbs go off for entire teams about how things are getting done today. It's a masterful process. It's fun to watch."

4) Look Beyond the Numbers

Babson uses a scorecard to assess each response. That covers "multiple factors" forming the backdrop of the rating for each RFP response: whether the vendor has met the requirement, the pricing, the financial background and stability, and the vendor's experience "with customers like us." While the result is a numeric score, the evaluation can also become "a little more subjective," Betts said.

When it's applicable, the college invites finalists in for demos and discussions, which also become part of the scorecard. "At that point we probably have enough information to start to make a decision," Betts said. "We might narrow it down — call references and do some due diligence on the financial background of the company." Due diligence is easier to perform with public companies than with private ones, "but we do our best," she added.

Then the project team is ready to make its purchase decision.

While all of that may sound like an unbearably time-consuming process, Betts estimates that most IT acquisitions take between 90 and 100 days from end to end, including the time dedicated to doing the requirements gathering all the way through to a fully negotiated and executed contract. "Our philosophy here — and mine in particular — is that the more work we do up front, the better it is for the project," she said. "The more prepared we are before a vendor comes in, the smoother a project is going to go."

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.