Blockchain: Letting Students Own Their Credentials

Very soon this nascent technology could securely enable registrars to help students verify credentials without the hassle of ordering copies of transcripts.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 03/23/17

While truth may seem evasive on many fronts, a joint academic and industry effort is underway to codify it for credentialing. At the core of the effort is blockchain, a trust technology developed for bitcoin and used in solving other forms of validation between individuals and organizations. Still in its nascent stage, the technology could, within just a year or two, provide the core services that would enable schools to stop acting as if they own proof of learning and help students verify their credentials as needed — without waiting on a records office to do it for them.

Basics of Blockchain

Blockchain was created by Satoshi Nakamoto, the same elusive figure (or figures — nobody knows) who developed bitcoin. Included in the original source code of that cryptocurrency, blockchain acts as a medium for exchanging value in a decentralized community without having to go through a third party. "Trust is hard-coded into the platform," as father-and-son writing team Don and Alex Tapscott explained in a Time article. "It acts as a ledger of accounts, a database, a notary, a sentry and clearing house, all by consensus."

In the bitcoin realm of business, blockchain dangles the promise of eliminating the middleman that takes a cut of every financial transaction anybody ever does while still maintaining a permanent record of the activity. As an article in the Economist stated, bitcoin has to be "able to change hands without being diverted into the wrong account and to be incapable of being spent twice by the same person." Traditionally, banks and that ilk have handled such record-keeping so that the rest of us don't have to. Blockchain sidesteps that, offering a way for people who don't know or trust each other to interoperate. It does this while keeping a record of the truth that is in no one person's control, but can still be confirmed or validated by those individuals and others they share the transaction details with.

The "block" part of a blockchain contains a given transaction hashed up with a bunch of other transactions generated by other users. Every few minutes, a new block is added to the chain, which maintains a record of every transaction ever made on it. The first blockchain transaction, known as the "genesis" block, took place on Jan. 2, 2009. Eight years later (as of March 15, 2017), the blockchain is over 106 gigabytes in size. Nobody can reverse the chain or go in and add corrections; they can only add new information that is subsumed into blocks and linked to the chain.

Early Birds

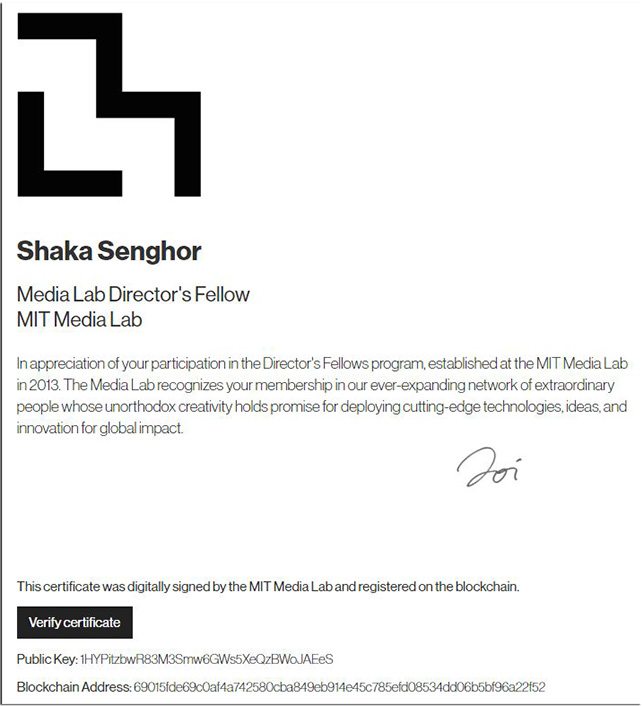

After a number of prototyping projects, in 2015 MIT began issuing blockchain-based alumni certificates to people who had participated in its Media Lab community. In 2016, it issued similar certificates to students attending an MIT boot camp on global entrepreneurship in Seoul. The goal of these endeavors has been to gain some real-world experience with blockchain and generate user feedback. In 2015, for example, the certificates were digitally signed by the Media Lab and registered on the blockchain. The public key for each of the certificates — like this one issued to Lab participant and best-selling memoirist Shaka Senghor — was a 34-character stream of numbers and letters that could be publicly verified on Blockchain.info.

A blockchain-based certificate from MIT's Media Lab

Then in October, as a second giant step, the Media Lab launched an open standards toolkit through its "Blockchain Certificates Project" (Blockcerts), developed in partnership with Learning Machine. The latter is a startup that's developing an ecosystem of products and services to help universities, companies and even governments use the public blockchain infrastructure to notarize official records. The toolkit consists of libraries for creating, issuing, viewing and verifying blockchain credentials — the same routines MIT tapped to issue its certificates.

The toolkit heralds "an entirely new infrastructure of trust for the 21st century," asserted Chris Jagers, co-founder and CEO of Learning Machine.

Right now, by the looks of things, working with the blockchain toolkit is best left to code plumbers who know their way around GitHub. But, according to some observers, it won't always be that way.

When Blockchain Heads to Campus

In a university setting, the concept of the blockchain is to give people "full control over their trusted credentials and transcripts," as Natalie Smolenski, a cultural anthropologist at Learning Machine, has written. The job of the blockchain, after all, is to keep track of three items, she noted: "the value itself, who conferred it and to whom it was conferred." Whether that's a monetary value or a degree or competency value is irrelevant to the protocol.

Figuring out this sort of credential transfer is important in an era when employers are moving away from the idea that the four-year degree is the final arbiter of a person's abilities. Digital credentials are making their mark in multiple areas, and blockchain could offer a simple pipeline for job candidates to share with hiring managers what they've learned, with undisputable proof of the earning built right in.

What does that look like on the ground? John Papinchak, registrar for Carnegie Mellon University, likens the future acceptance of blockchain to the previous adoption of the National Student Clearinghouse. In 1993, what was then called the National Student Loan Clearinghouse was set up as a nonprofit by a group of colleges and universities that wanted to simplify enrollment reporting for student borrowers by automating the process of student record verification. Now, 3,600 institutions use the Clearinghouse for its original purpose and additional ones, such as handling electronic transcript processing and related transactions. Yet use wasn't a foregone conclusion for everybody.

The same reticence that greeted the Clearinghouse is bound to slow adoption of blockchain, suggested Papinchak during a panel session at Educause's annual conference in Anaheim last year. "If it's standard and easy to use — particularly for employers and schools — then it's going to catch on and folks are going to want to take advantage of it," he said. Right now, however, in the registrar world, blockchain is "definitely a big unknown."

Blockchain will be of particular interest to this specific segment of the higher ed community because it will greatly simplify how credentials are shared with the recipients. Ease of use will be the big draw, Papinchak offered, especially when the credentials need to be issued to "thousands of students or hundreds of weekend workshop participants. Presently, we don't have an easy way to report that relationship."

Simply "putting something out there on the internet" (think "digital badge") can be "disconcerting" to school officials, Papinchak pointed out. "Blockchain makes us more comfortable. One nice thing about this type of platform is that it does have those securities — did this institution issue those credentials to this person?"

On the recipient side, blockchain puts the student in control of his or her credentials. While the school will still maintain an official copy, the student's version of it can be shared, just as with the MIT example, by supplying public keys to prospective employers, who can verify the credential themselves. "That's it. No school, vendor or institution has to be consulted at any point during the verification process," asserted Jager. "The student has a convenient way to use their academic credentials, and employers have an immediate way to view and verify those claims."

Of course, that's also the part that Papinchak believes will generate the most naysaying among his peers. "There are going to be some registrars who are going to be afraid of this: Basically, I am giving [students] control of the transcript. [They] don't have to order it and pay for it. That's a source of revenue we're going to lose."

His thinking doesn't bend that way. "Isn't it better to lose those nickels so our alumni can have those transcripts for when they need them? This allows them to have much more fluidity in that whole process. This puts the record in the alumni's hands, so they can take advantage of that."

Titleholders of Learning

Among Learning Machine's tools is a wallet app that allows a person to carry blockchain-based credentials on a smartphone and share them on the fly. If the phone gets lost, the proof of certification or degree can be regenerated by using a pass phrase. Although the app is practical, it also serves as a demonstration of the possibilities for blockchain. The organizations involved in the effort hope that in the not-too-distant future blockchain functionality will be picked up by ed tech companies and built into their products. Pass a class? The student information system will automatically issue verification to the student, who can turn around and add the achievement on a digital job application. No trusted intermediary needed.

Before this current semester ends, Learning Machine hopes to launch a commercial app — a graphical interface for issuing and tracking the use of certificates for use by registrars. According to Jagers, the company is designing certificates and doing "integration engineering," allowing schools to issue credentials. "The product is ready and we're in the midst of configuring pilots for our first wave of schools, with MIT leading the way," he said. "Interest has been high and we're already building a waiting list."

When that day arrives, it could go down in the annals as a milestone. Students truly will become titleholders of their own learning. "Who really does own the degree?" asked Papinchak. "As a society, I think we're seeing the transfer of that from the academy to the student."

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.