Education Trends

Page 2 of 3

How to Be an Ed Tech Futurist

Working in educational technology often means coping with change. New technologies frequently appear, institutional dynamics mutate and user populations gradually transform. When we grapple with these changes we invoke the assistance of many fields, from computer science to organizational psychology and even therapy. I would like to nominate an additional discipline to help technologists working in education: the futures field, also known as forecasting.

Humans have been imagining our future for millennia, using techniques as varied as science fiction, betting and divination, but the futures field as we know it today dates only to the mid/late 20th century. That's when several visionaries working in business and the military, such as Herman Kahn and Pierre Wack, began codifying forecasting as a set of methods. Those methods have since been honed, extensively studied by scholars, supported by professional associations and deployed internationally.

Before we survey those methods, it's essential to acknowledge several futures problems and limitations. There is no reliable way to predict the future. Indeed, many futurists shun the word "prediction." Instead they see their work as opening up multiple future possibilities, with a careful eye on event probability and possibility. Moreover, forecasters, like the rest of the human race, can be blindsided by what essayist and risk analyst Nicholas Taleb dubs "black swans": events that have a very low probability of occurring, but when they do have enormous impact. (For recent examples think of the 9/11 attacks and the 2008 financial crisis.)

Trend Analysis

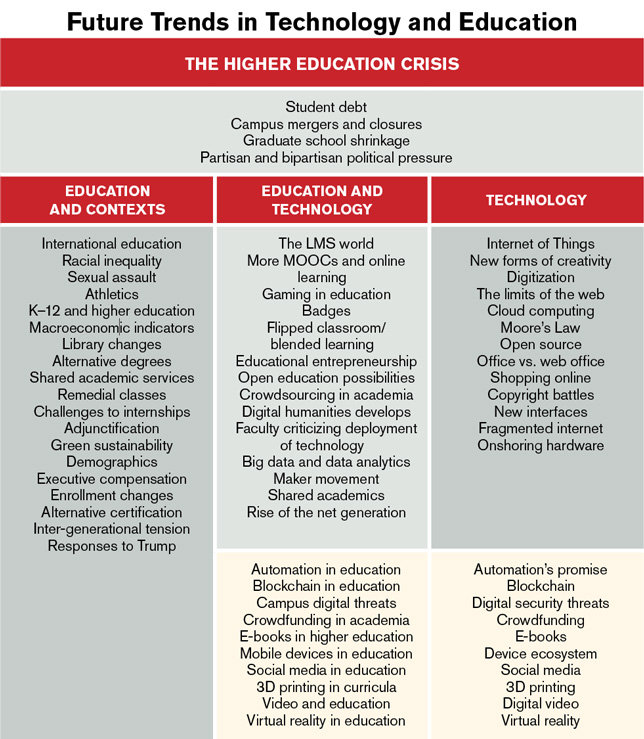

To begin with, a leading futures approach focuses on analyzing present-day trends to explore their downstream impact. This involves identifying and documenting forces that help shape the present situation. For technology and education, these change drivers include a variety of forces, from rising demand for video (both consuming and producing), to an aging population, to deepening use of mobile devices. We can quantify the shape of these trends, then extrapolate them. An example of this method is my Future Trends in Technology and Education (FTTE) report, which has tracked and documented more than 80 trends since 2012. I build and share FTTE-driven extrapolations through presentations, blog posts and publications.

Trend analysis has several advantages, starting with realism. To understand a trend, we have to look carefully at the real world, including both qualitative and quantitative information. To some extent campus offices already do this, and many are looking to expand that data-gathering. Trend extrapolation can be useful for thinking through drivers that are not changing dramatically, but gradually. However, not all drivers follow linear progressions, meaning trend analysis is not a universally applicable method.

Environmental Scanning

Identifying trends is no small feat, and actually constitutes a second futures method, usually referred to as environmental scanning. As the term suggests, this approach involves scanning for emerging trends and developments. At a very basic level we all do this through being aware of our immediate environment, keeping up with the news and participating in professional development. Environmental scanning goes beyond this, starting with scale. Scanners check dozens or hundreds of sources, including blogs, videos, news feeds and even print materials. They take care to set up a diverse source set, varied by viewpoint, demographics, geography and other influential perspectival factors.

Environmental scanning has advantages akin to those of trend analysis. Scans are grounded in present-day reality, rather than speculation. Conducted well, they broaden participants' and consumers' worldview. Gathered over time, scans point out trends, which can then be tracked. Two good examples of this method come from the library world: a 2015 scan conducted by the Association of Research Libraries and a 2010 report from the OCLC Online Computer Library Center.

Scenarios

A third forecasting approach differs from trends and environmental scanning in being more qualitative and theatrical: We can create scenarios that depict potential futures, each one driven by the impact of one or two trends. Scenarios are not predictions but stories of what might occur. They are also heuristic tools, as they let us think through how our institutions and our own professional lives might change if certain developments come to pass. For example, a scenario could posit that scholarly publication and textbooks "flip" to an open model; how might that change a campus library, classes, student financial aid, faculty publishing and research, tenure and promotion?

Scenarios offer all of the human benefits of storytelling, encouraging us to engage personally with a vision. They can elicit greater participation than trend data, depending on the audience, due to their narrative structure and creativity. They help flesh out strategic planning. Their largest downside is that they can be time-consuming to interact with, especially when a group works with multiple scenarios.

Science Fiction

While scenarios are stories we create about the future, there is another realm of professional storytelling along these lines: science fiction. The genre of science fiction has, after all, been offering visions of what might be for centuries. Not only has this offered obvious aesthetic and cognitive benefits to large audiences, but science fiction has also influenced technology. Consider the flip phone, for example, which draws on the Star Trek communicator. During a court battle over the iPad's invention, Samsung fought Apple to a standstill by demonstrating that tablet computing appeared before a massive audience in the 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey — a generation before the iPad's first release. John Brunner's Shockwave Rider (1975) portrayed a world reshaped by networked computers, where hackers released worms to wreak havoc on other people's code, and virtual gambling and education were established realities.

More recently we have seen even more examples of science fiction envisioning and perhaps shaping the future. Computer interface designers were inspired by devices in the 2002 Steven Spielberg film Minority Report. Vernor Vinge's award-winning 2006 novel Rainbows End portrayed a school system reshaped by mobile devices, augmented reality, book scanning, drones, makerspaces and project-based learning, a scenario which we seem to be entering in 2017. Meanwhile, a burgeoning subgenre of "climate fiction" helps us imagine the world after climate change. Science fiction might be one of the most effective, and certainly entertaining, tools in our forecasting toolkit.

Synthesis and Collaboration

All of these methods are available to a campus technology office. An educational technology team, for example, can write scenarios about future pedagogy for faculty and support staff to consider. An IT group drawn from different teams and functions could collaboratively track trends they deem most significant. An inter-office task force could conduct an environmental scan.

These methods can be used in isolation, or in new contexts and combinations. Trend analysis can reveal fruitful drivers for scenario creation. Students can write scenarios which faculty profitably consider, and which inform a library's strategic planning process — itself integrated with that unit's ongoing trends analysis.

Beyond a single institution, there are many ways for us to collaborate in futuring practice. The local community can offer many thoughtful collaborators with a variety of backgrounds, from business to nonprofit to the military. Schools can draw on published educational futures work, like the New Media Consortium's Horizon Project. Consider, too, the benefits accrued to environmental scanning by comparing discovery across different geographical locations or institutional types. Faculty members can productively cross disciplinary boundaries in imagining the future of education.

Technology can play many roles in strengthening our futures work. Digital tools make it easier for us to create multimedia objects, such as scenarios in video (e.g., Richard Katz' "EDU@2025," or Michael Wesch's "Rethinking Education") or through podcast (such as FlashForward). Tech makes it easier for us to draw on a wide range of sources through RSS readers or Twitter lists, preferably informed by digital literacy. On social media we can follow future-oriented professionals, inventors like Ray Kurzweil, scholars, or futurists like Amy Webb and Jamais Cascio. We can use computer games to model possible futures (for instance, see the University of Iowa's Iowa Electronic Markets tool). Perhaps most powerfully we can use the internet to share our thoughts and discoveries with a potentially wide audience, garnering feedback and more ideas.

These methods can offer campuses thoughtful and practical benefits as we face institutional and technological change. They can help us anticipate new developments, while giving us time to think through how we can best prepare for and respond to them. Futuring provides us with new ways to collaborate and connect — virtues sorely needed in 2017. From trends analysis to scenarios, science fiction to horizon scanning, forecasting not only gives us ways to imagine a better world, but also tools to help build one.