Fostering Tech Skills Through Community Outreach

A program at the University of Texas at El Paso is transforming the K-industry pipeline through hands-on STEAM experiences — and giving college students a chance to contribute to local schools.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 11/07/18

Category: Teaching and Learning

Institution: The University of Texas at El Paso

Project: Tech-E Outreach Program

Project lead: Michael Pitcher, director of Academic Technologies Learning Environments

Tech lineup: 3DPrinterOS, Apple, Ozobot, Raspberry Pi, Ultimaker

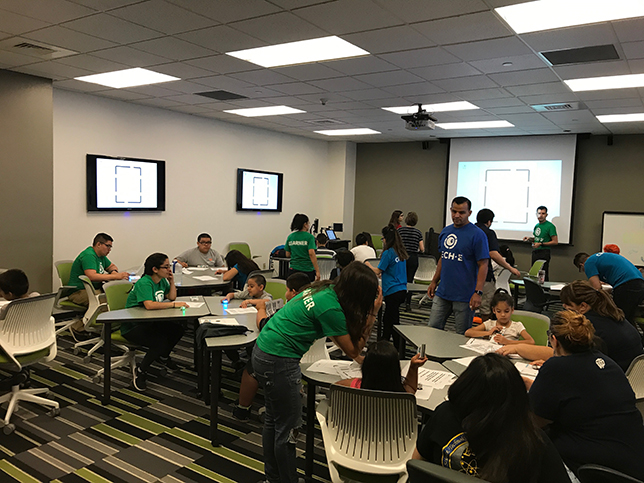

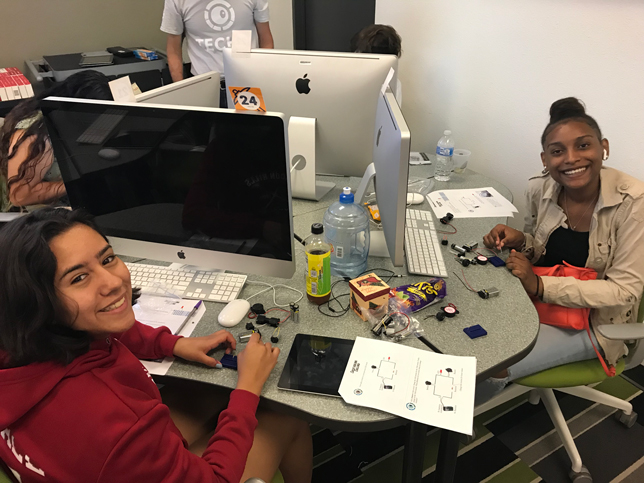

In UT-El Paso's Tech-E outreach program, college students serve as mentors and guides on the side for local K-12 students.

Sometimes, doing something for others delivers just as much impact for the doer as for the recipient. That has been the case for the University of Texas at El Paso, which reached out to local K-12 schools to provide a week-long technical summer camp for students without other options and ended up with a program that runs year-round and educates 50,000 students a year. Tech-E ("techie") Outreach, as it's named, has also helped the college students involved to gain confidence in soft skills, boosted their understanding of technical content and provided a way for them to feel like they're already contributing in their chosen fields.

From Modest Beginnings

According to Michael Pitcher, director of Academic Technologies, and Pedro Espinoza, instructional technologist, a departmental conversation about how college students often struggle with issues related to self-esteem and soft skills led to talking about how the kids in their city face similar problems. Often, kids might be great at computer science or engineering, but didn't necessarily believe they had what it takes to succeed — especially when their families couldn't afford to send them to a summer camp where they might develop those skills. As a group, the people around the table decided they'd volunteer their time and run their own camp for a week.

Outreach to area teachers unstoppered a hidden need. "We were thinking that if we got 12 kids, we'd be ecstatic," recalled Pitcher. "A ton of people applied." In response, the group opened two additional camps that summer. And by the following December, teachers were already lining up with new candidates for the following summer. By February the upcoming camps were filled up too, and there was a wait list.

And then, the team fielded interest at the district level. School leaders saw what the students were like who had been exposed to the camps, and the school system was interested in piloting a program delivered for the whole school year. While Pitcher and his group envisioned testing out the idea on a single school and maybe 75 students, the district had a different idea: bringing in 400 students. "We asked ourselves, how can we grow this? We sat down for a long couple of days and nights, and we said, 'OK, let's do this.'" The program was formalized; funding issues were hammered out; and it became part of the rotation for people in the Academic Technologies division, which recruited student volunteers to help deliver the content.

Months later, the district decided it wanted to add a second cohort, and then a third. And it suggested turning the year of training into a multi-year program that would continue growing ever after, all the way from second grade to the end of college.

How Tech-E Works

Nearly every Friday during the school year, the buses start arriving to campus. Loads of students, primarily in grades 2-8, step out to be greeted by their college mentors. These are university student volunteers from engineering, science and other degree programs who will stay with the kids throughout the day and move from session to session, acting as helpers, guides on the side and lunch companions.

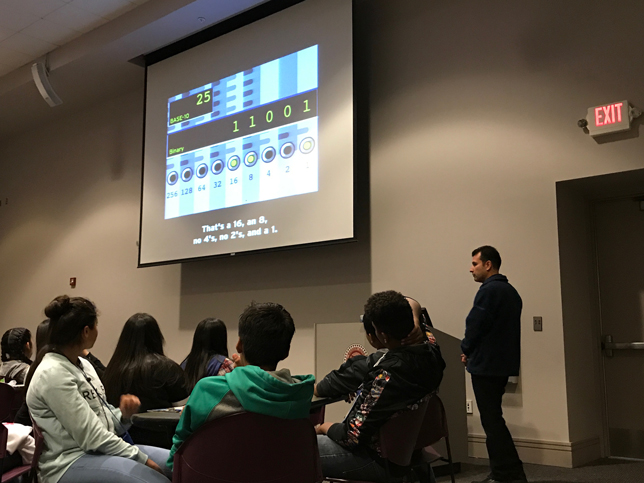

Kids learning to convert binary numbers to decimal

Following a quick welcome and overview, grade-level groups are split into sections, which rotate through four workshops during the day. Each grade may be learning the same topic, but the lessons are tiered to incorporate more challenges and higher-level activities. For example, while the second graders might learn how to convert binary numbers to decimal and back again, middle schoolers and high schoolers might apply that formula to cryptography or computer signals or other real-world uses.

A given class comes to the UT-El Paso campus every nine weeks. Teachers come in ahead of time for professional development to help them "fully understand the material," noted Pitcher. Then after the on-campus experience, students return to their regular classrooms, where teachers lead additional activities to help tie the topics to the rest of the curriculum. For example, if the subject was block programming, the teachers would apply the same logic to history: This happened, then this happened, then this. In that way, said Pitcher, "Students really start to understand the concept not just in computer science but in a more generalized context." The teachers also share feedback on how their classes are doing so that the university team can adjust the program for the next campus visit.

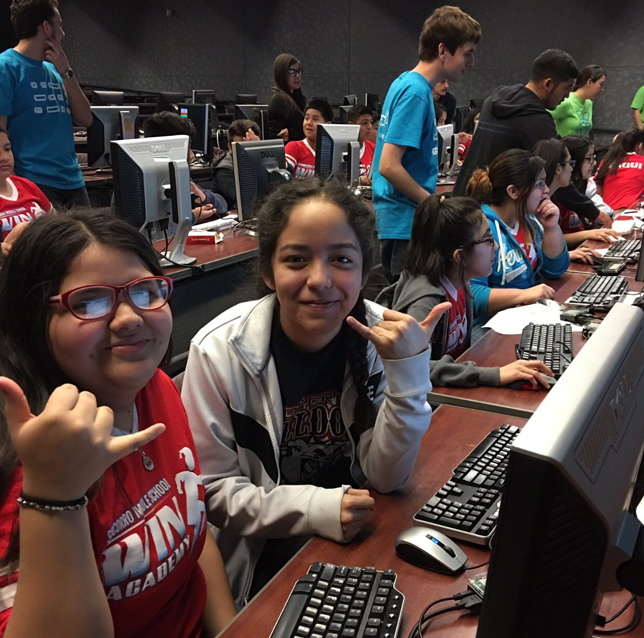

WIN Academy 7th graders working on an IoT activity

One district that's immersed in Tech-E is the Socorro Independent School District, which sends its WIN Academy students from numerous schools through the program. These are learners who haven't succeeded in a traditional school setting. As Pitcher explained, "The kids who work with us are the ones should pass standardized state tests but, for whatever reason, they haven't. They are selected for a more hands-on approach. They get the concepts; they just have a hard time testing on it. They do much better at applying the concepts than they do at testing on the concepts."

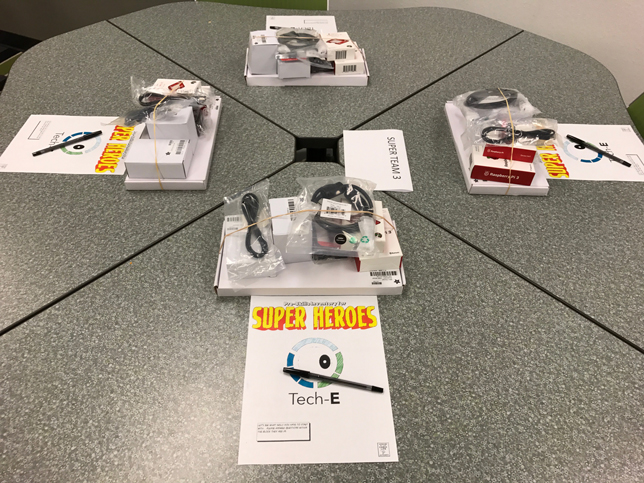

Raspberry Pi activity

And that's exactly the emphasis for Tech-E: College-level activities are broken down into "key basics" and then applied. Once the students understand binary conversion, they might move into circuit design and play with electronic components to learn how electricity works. From there they might build a Raspberry Pi kit, which they can take back to school with them. Other technologies in play include Ozobots for robotics and coding skills, 3D printing gear and Apple tools. In addition, speakers from industry and research labs come in and share their stories with students, to give them a sense that they too can pursue college degrees in technical fields.

Ozobots are used to engage students with coding and robotics.

At the end of the school year, students attend a challenge day in which they must navigate a series of real-world problems that require them to apply their knowledge to industrial challenges such as stopping a hacker on a network, creating a Python script or automating a smart home. These challenges are scaled in difficulty for various grade levels.

Students work on a circuit building challenge.

The University Impact

While there's a direct impact on the K-12 students exposed to the courses (according to pre- and post-program assessments about three-quarters of participants master the concepts making up the learning outcomes), the university is a major recipient of benefits as well.

First, there's the personal development of the 60-odd students volunteering to work with the kids. "Not to pick on the computer science or engineering students, but a lot of them struggle with verbal skills and communication," noted Pitcher. "If they can take a really high-level concept they've attained in class and teach a second grader, it's less stressful for them to give a presentation on that concept."

Also, many of the students find the experience of working with the younger students "enriching and helpful," said Espinoza. "These students gain experience teaching, because they give workshops and help them one-on-one. And they become mentors. [The younger] students see them as resources and look up to them."

Plus, the college students gain a sense of satisfaction that can be elusive when they're just starting out. "Sometimes as a freshman or sophomore, you're like, 'OK, I have the basics, but how can I get more involved?'" asserted Pitcher. "This empowers our college students to feel like they're already making a difference in their fields. That builds confidence."

Then there's the college student who worked with the program and graduated, became a teacher and brought her own class to participate, said Espinoza. "That's worked full circle there." Another teacher was so captivated by the program, she decided to pursue her master's degree in education leadership so that she can bring Tech-E to a broader audience in her district.

Now the university is considering recruiting in its education program so that future teachers can work with the youngsters for a couple of semesters before going out to a district for their pre-service experience. The advantage, Pitcher pointed out: They'll "get a real feel for what it's like to deal with kids in a classroom environment teaching technology on a wide range of stuff. That's less investment than waiting until your junior or senior year to find out if you really like to do this or not."

Empowering the Younger Generation

Another promising outcome of the program is how it could help mold the freshman experience. "We know a good percentage of the kids coming to our college are coming from our local K-12 districts. Having a better understanding of their struggles and what they're doing really helps us better prepare for those college students," explained Pitcher. "We can set more real-world expectations of what our students are going to be lacking and how we can help them develop along that path."

And, of course, added Espinoza, the K-12 students participating today will become college students eventually and that'll give them the chance to come back and help out themselves. "More than likely, some of them will be playing the same role as our current college students are in empowering the younger generation."

Return to Campus Technology Impact Awards Home

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.