STEM Education

Why Build a Boot Camp?

Ever-increasing numbers of universities and colleges are teaming up with boot camps to deliver tech training. Does your campus need one too?

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 01/23/19

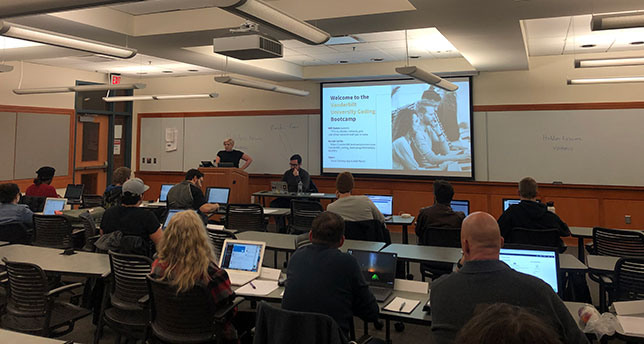

Vanderbilt's Coding Boot Camp (Photo: Vanderbilt University Coding Boot Camp)

When Doug Schmidt persuaded his institution to sign on with Trilogy Education Services to launch what has become known as the Vanderbilt University Coding Boot Camp, he considered it one more step forward in a 16-year effort to help improve the technology economy in Nashville, where the university is located. As this professor of computer science and co-director of the Vanderbilt Data Sciences Institute noted, everywhere else that he's lived, worked and taught — Southern California, Northern California, Virginia, St. Louis, Maryland — has "had a really thriving tech ecosystem." In Nashville, however, small companies, primarily in healthcare, have dominated the tech scene, making for limited opportunities for the school's graduates who might want to stick around.

"Getting more workers here with technical skills makes it easier for companies to move here because they can find a workforce — which in turn makes it more credible for good tech people to move here because the companies are here," Schmidt explained. And while Vanderbilt has grown its computer science program to about 550 majors and 150 minors a year, it's still inadequate for the needs of a city with between 3,000 and 4,000 unfilled tech jobs.

"The motivation here has always been to build the workforce," Schmidt said. "There's this huge demand for talent. Having a good tech environment is great for everybody. And so that was the pull."

The push was the opportunity to work with Trilogy, which specializes in helping universities create a form of continuing education program in "hot tech topics." In mid-January 2019, Vanderbilt kicked off its first cohorts: two separate sections of web development, twice what the institution expected to have at launch. The program lasts for 24 weeks, costs participants about $11,000 and is hosted face-to-face in campus classrooms. Those who finish successfully earn a certificate. But more importantly, they gain access to Trilogy's own career services, which helps them plug into local opportunities for "better paying jobs that will help them support their families," as Schmidt put it.

Vanderbilt is just one of 40-plus schools that have signed agreements with Trilogy to deliver an intensive education in web development, data analytics, user interface design and cybersecurity. Others include University of California, Berkeley, University of California, Los Angeles, University of Central Florida, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Pennsylvania, Columbia and Georgia Tech. And while Trilogy is arguably the largest company in the boot camp space partnering with higher education, it's not the only one.

Revature, which pegs itself as a "leading-edge technology solutions firm," takes a different approach. Working with its own A-list set of set of institutions (including George Mason University, Ohio University, Arizona State, California State University and the University of Missouri), this company sets up classrooms on campus, then recruits students to take a free, 12-week crash course in coding with a guarantee of employment as a software consultant at the end.

A Meeting of the Minds (and Models)

According to Liz Eggleston, co-founder of Course Report, which monitors the boot camp market, it's a sure sign of maturity that boot camps and universities are working together. A few years ago, when the boot camps first began gaining traction, there was a rivalry between those promoting formal computer science degrees and those endorsing the considerably shorter training programs that prepared students to quickly pick up work as full-fledged developers.

Now, noted Eggleston, there's a meeting of the minds. "Boot camps are getting a bit more mainstream and education is becoming a bit more flexible and skills-based and actually training students in skills they need to get jobs."

They're even learning from each other. She pointed to the recent news about Make School and Dominican University of California, which are working together to design a CS minor at Dominican, featuring both tech and humanities, to cover the hard and soft skills employers want from new hires. In return, Make, which offers coding programs, received accreditation through Dominican for its two-year bachelor's degree in "applied computer science."

"There are so many different types of partnerships between the schools," said Eggleston. But it comes down to this, she pointed out: "Boot camps get the panache of working with the university and universities get the trendy, cutting-edge skills that a boot camp is teaching."

Eggelston, who monitors such deals, has identified a number of formats followed in these partnerships:

- On-campus and open to the public. The outside operator comes to the school to deliver its programming, typically after hours and on weekends, with its own curriculum and instructors (although faculty from the hosting school might weigh in here and there). This is the model followed by Trilogy, which argues that it isn't a boot camp but rather a "workforce accelerator," because it has no physical location of its own from which to deliver programming.

- Off-campus and open to the public. The boot camp hosts classes at its own facility, but the institution drives prospects in its direction. This was the model followed by the University of New Haven and Galvanize before that was shuttered, about a year ago.

- On-campus and open to students. In the Revature model, after free training, students are hired by the training company. A similar program exists at Carleton University, which has teamed up with Shopify to provide multi-year internships to CS students that cover their tuition and pay a salary.

- Online or blended boot camps open to the public.This model is followed by the Software Guild, which works with University of Georgia and several other institutions to market the program. A blended option includes some face-to-face instruction on campuses.

- Integration with existing degrees. Florida's Lynn University works with Wyncode Academy to integrate the boot camp experience within master's programs. Students going this route pay both entities but receive credit towards their degree.

- Internally launched boot camps. Northeastern University's Level, developed by the university, is a prime example of this. Level students may earn transferrable credits for specific master's programs. They also gain access to the university's career services, job fairs and some professional-studies-related scholarship funding. The format includes full-time, part-time hybrid, part-time virtual and self-paced options.

One other model is still limping along. Under the Obama administration, "Educational Quality through Innovative Partnerships" (EQUIP) began a limited number of pilots to encourage colleges and universities to work with "non-traditional providers of education." The goal was to allow students — especially those from low-income families — to apply their federal student aid to cover the cost. In April 2018, the first institution finally received plan approval to begin enrolling students. The fact that it took so long to get to launch doesn't bode well for the program's future, said Eggelston. "The bureaucracy of those types of programs is just so much — it takes so much longer to get off the ground than what we're used in the coding boot camp world, where students are graduating every three months."

Boot Camp Benefits

At one point Course Report counted some 600 boot camps operating around the world. That has since consolidated: Now the count is closer to 90. But even so, noted Eggelston, "The number of graduates is increasing year over year."

It's no wonder that so many boot camps have materialized, explained Louise Ann Lyon, senior research associate at ETR, a research company that focuses on health equity: They're filling a perceived vacuum in the education segment. "Universities are focused on grades and how to assess what students are learning, whereas boot camps are like, 'It's up to you. You're coming here because you're interested in learning the skills. We'll give you tools, but we're not going to sit around and assess if you've learned this and give you a grade and worry about cheating and all those kinds of things.'"

While the biggest benefit of boot camps is that they offer a ready pipeline to hiring companies and well-paying employment, that isn't the only way they can enhance college CS programs. In a National Science Foundation project undertaken by ETR and the College of Charleston, researchers also identified several other values:

- Boot camps focus on the latest technology;

- Instruction uses experiential learning and hands-on practice;

- Soft skills are a big part of the curriculum alongside the technical work;

- Students work on real-world projects; and

- They achieve greater diversity.

That last point can't be over-emphasized. With well-nigh every institution in the land declaring its pursuit of women for STEM study, bootcamps are succeeding wildly. According to Lyon, who serves as principal researcher on the study, around 35 percent of boot camp graduates are female compared to just 14 percent for bachelor's programs in CS. Why the difference?

What women told her research team was that either they were "turned off by CS" or the college-level classes they tried were so "dominated by men," they felt "uncomfortable, intimidated or uninterested" and they chose to switch majors. (As Lyon put it, "You can get through six months of something, but four years of being the only woman in the classroom is harder.") Then, when the women moved into careers that required technology, they found that programming or related skills were "the favorite part of their work" or they realized that it could be "a direction they could go to get a better job."

Rather than going back to university for a second bachelor's, women found that boot camps could provide a "super-intensive" program to teach them the skills they needed in a short amount of time. "They didn't know about it, really, and then they found they really liked it, so they looked for a quick way to get more of those skills and be able to move in that direction," Lyon said.

What Universities Have to Learn

Before your college jumps into a deal with a boot camp, due diligence is in order. After all, Lyon pointed out, "This space can be complicated." Even the term "boot camp" encompasses a lot of different kinds of operations. "Some are in person, some are online, some are 10 weeks, some are two years." Her caution: "Be a little careful when you use that term, because it actually encompasses a lot of different models and institutions, some of which are more successful or better than others. You can't generalize too much."

Her advice is to consider the tradeoffs. "If you incorporate a boot camp, does it mean students are not getting as much theory in classes that maybe could help them later? Are you focusing more on the skills and less on the theory, and does that have some disadvantage?"

Then there are the faculty concerns for their students. "A lot of them are interested in how they can serve students best," she asserted. "Is there something happening in a boot camp that helps serve students and what could we learn and incorporate from that?"

Eggelston said she believes the big lesson is fairly obvious. Colleges and universities need to put a heavier focus on student outcomes — specifically, employment. "While a university may not as be as super-accustomed to actually getting a student a job when they graduate, that's what people expect from a coding boot camp. If they pay that money up front, they're going to be ready and introduced to a job when they graduate."

Vanderbilt's Schmidt could envision a marriage of the two kinds of education providers that plays directly into university gaps.

He'd like to see the people taking the boot camp courses at his institution working with the on-campus business incubator The Wond'ry. By teaming up students in the coding classes with those entrepreneurs, the boot camp students would have the chance to work on actual projects and the people who pitched the ideas would get the help they need.

Or take the graduate in some "nondescript major," pursuing a given topic because it's their "intellectual passion," he offered. Nothing would prevent a senior nearing the end of that degree program to enter the boot camp as a last semester effort. "They could finish up by the time they graduated, and they could do it in evenings and weekends, which is not going to conflict with classes. They'd obviously have a time management issue on their hands, but leave that aside. If you're sufficiently motivated, you would perhaps have the best of all worlds. You'd have a Vanderbilt undergraduate degree and a skill that you could parlay in the workforce very quickly."