Improving Online Teaching Through Training and Support

Kapi'olani Community College instituted comprehensive training to help faculty design, develop and assess online courses — including supportive incentives to make sure instructors can successfully complete the program.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 10/30/19

Category: Teaching & Learning

Institution: Kapi'olani Community College

Project: Teaching Online Prep Program (TOPP) and Teaching Equivalencies (TEs)

Project leads: Helen Torigoe, instructional designer; Youxin Zhang, instructional designer; and Jamie Sickel, instructional designer

Tech lineup: Adobe, Flipgrid, Loom, Padlet, ProctorU, Sakai, Screencast-O-Matic, Zoom

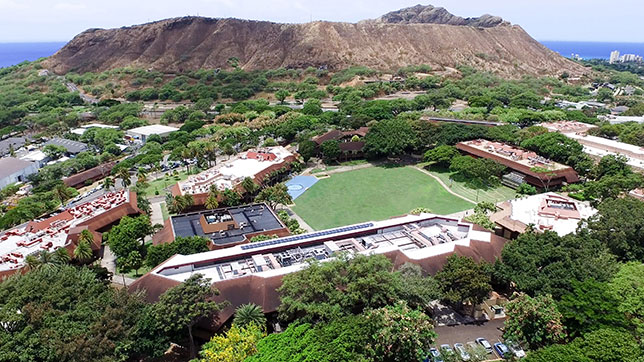

Kapiolani Community College

At Hawaii's Kapi'olani Community College on the island of Oahu, a growing demand for online courses sparked a need for more faculty training, to help instructors create or convert their courses for online delivery. So when Instructional Designer Helen Torigoe was asked to "do something about training the online faculty," she looked for a way to scale her experiences at a previous campus working individually with online instructors. When online instructors struggled through building their courses, she recalled, what really helped them was when they could see the course from the perspective of a student.

Torigoe decided that if she could create a program that would help those instructors engage in their training as students themselves, the "lightbulb" might go off for them. "I wanted to create an environment where they could come out with something that they can use right away," she explained.

The result, the Teaching Online Prep Program (TOPP), is a faculty professional development program put on by the Center for Excellence in Learning, Teaching and Technology that places a group of participants into a mostly online course on Laulima, the institution's instance of Sakai, which serves as a model for what they're creating themselves. Among the technologies used in TOPP: Zoom, for synchronous online class meetings, office hours, group project meetings, presentations and screencasting; Padlet, for collaboration and building an online learning community; Flipgrid, for building an online learning community and facilitating collaborative learning; Adobe Spark, for creating custom graphics and videos; Loom and Screencast-O-Matic, for screencasting to create instructional videos; and ProctorU, for online proctoring of exams and student identity verification.

As Kelli Nakamura, an assistant professor in history and a member of the first TOPP cohort, described, "We participate in the course and at the same time we're paralleling it, modifying it and creating our own course, utilizing those kinds of skills." For example, she noted, "we'll use the lesson pages and try to replicate it." The same goes for discussion boards, videos, open-ended questions and other instructional activities.

Project leads Youxin Zhang, Helen Torigoe and Jamie Sickel

The instructional design team (now grown to two and a half people) has access to the courses as they're under development to provide "immediate and continuous" feedback, said Torigoe. Likewise, there's a lot of sharing within the faculty cohort, such as in the area of course planning, to help spark a "learning community of practice."

By the time the TOPP training is done, the instructors have gained an understanding of best practices for online course development, a better grasp of instructional design principles, access to others who are doing the same kind of work they're doing, and actual course content. That last element is what has made the "real difference" from other training courses, Nakamura emphasized. "We [come out of it with] something that we're going to literally be using either the next semester, in a few weeks or the following semester after that."

No Teacher Left Behind

Early on, TOPP drew in enthusiasts such as Nakamura, "who were anxious to improve themselves, improve their courses and take anything that was available to them," said Torigoe. But eventually the message came through from those who hadn't participated: Faculty needed more time in their schedules to accommodate the training.

During the regular academic year TOPP lasts eight weeks; in the summer, when people can devote more time each week to their course development efforts, it goes for six weeks. The time requirement is six to 15 hours per week, a hefty commitment for faculty who often have other administrative duties on top of their teaching.

Recognizing the success of TOPP, Leigh Dooley, distance education coordinator, promoted the idea of granting three teaching equivalencies (TEs) for TOPP participants. Instructors in TOPP training could effectively remove one course from their schedules. Passed by the faculty senate and approved by the administration, the TEs have been in effect for full-time faculty since 2018. As a result, interest in TOPP exploded.

Nakamura called it the "no teacher left behind" movement. The older faculty, "with incredible experience and knowledge," who may not be digital natives, now have the support of the administration to take "the time and opportunity" to learn how "to share that in an online environment."

Such training has also become mandatory for anybody teaching online for the first time. Those people who were already teaching online or who have taught online in the past were "grandfathered in," said Torigoe.

As it is, Torigoe's team has struggled to keep up with campus demand. While TOPP is taught in fall, spring and summer, the school may add a second summer session. And because there's now an expense affiliated with granting those TEs, the number of faculty has been limited to 10 per cohort, which the instructional designers are happy about. "We're not just teaching a class, but we're working one-on-one individually with them, giving them feedback, meeting with them and suggesting design changes and whatnot. So, there's a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes as well," Torigoe said.

On top of those activities, the design team has organized "Recharge" workshops to continue the learning, and Dooley has set up "spotlights," where the online faculty meet to hear from four or five of their peers about course strategies: how they've have laid out their courses, how they're teaching certain topics or facilitating elements like small group projects and forum discussions. Those are crucial, said Torigoe, because "there's a lot of learning that goes on at those sessions without any instructional designer being involved. They're really learning from each other."

Continuous Improvement

Just as TOPP training never really ends for its faculty participants, TOPP itself is always undergoing revision, said Torigoe. The crew would like to develop the next training, with more advanced techniques, which she referred to as "TOPP 2.0." But the next most critical step, she added, is doing course quality review built on TOPP. While the college has studied industry-standard frameworks for online courses, such as those from Quality Matters and the Online Learning Consortium, Torigoe expected that Kapi'olani would handle the rubric creation in-house, so that "it will really cater to our own faculty."

In the meantime, she insisted, it's too soon to quantify the influence of TOPP on student success. While some 80 instructors have gone through the training to create or recreate their online courses, they're really "still learning," Torigoe said. However, she doesn't want to discount the sense of "empowerment" faculty have expressed. "To me that's a lot more real evidence of the impact of the program. People will say, 'Oh, I was afraid of teaching online before TOPP, but now this has really given me so many ideas and tools and empowered me to be a more confident teacher,' or 'The navigation of the course is so clear now. Students love it.' That gives me a lot of excitement and also hope that we will be able to affect more online courses going forward."

Return to Campus Technology Impact Awards Home

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.