Google Inspires Excitement, Hesitation in Instructors

Google+ has become the fastest growing social network in history, in part because of its unique circles interface and video chat feature. Some instructors in higher ed see it as a great new collaboration tool, while others are still worried about privacy on the network.

- By John K. Waters

- 08/24/11

Google+ has accumulated more than 25 million registered users since it was launched at the end of June, making it the fastest growing social network in history, according to the Web watchers at comScore. That growth rate is even more impressive when you consider that it was released as an invitation-only beta project. The new social network generated immediate and intense interest, and the Web was, and still is, rife with blogs and tweets about how to secure one of the 150 invitations given to each of the project's initial beta users, and then bestowed on each of their invitees.

But reactions in higher education circles to Google's latest foray into social media have been mixed. There's a skepticism out there engendered by Google's earlier failures in the social media arena, as well as concerns about how the search giant will use the personal information collected on the network. But there's also a real enthusiasm for the social network's potential.

Alex Halavais, associate professor of communications at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, CT, and vice president of the Association of Internet Researchers, said he had high hopes for Google+ when he first began to explore the network, but he now says that it's not quite ready for higher ed.

"I had originally intended to make pretty heavy use of Google+ for courses this semester and next," Halavais said in an email. "I'll still be holding office hours in a Google hangout. It's convenient, I like the way it shifts to who is talking, and it works well for a handful of people."

It's the network's approach to managing groups that gives Halavais pause. He’s happy that the network keeps the title and grouping of its circles private by default, but he wants the ability to make circles public and the option of allowing members of a circle to add new people.

"It's incredible to me that Google has yet to implement a way of sharing circles easily," he said. "Several have suggested they be called squares. Right now, the logistics of trying to get a group to use Google+ efficiently is just too complicated. Everyone in the class would have to add everyone else to the same circle one-by-one. Not going to happen. I'd really like to become Google+- and Google-centric in my courses, but without an easy way of handling group functions, it's still a no go."

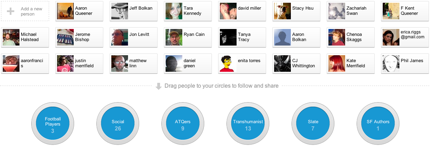

Circles is one of the most talked about features of Google+ among those considering it for implementation in higher ed. Unlike Facebook, which added friend lists late in the social network's life, the ability to divide contacts into groups (circles) and to control what information is shared in those groups is fundamental to Google+. And employing the Facebook feature is much more complicated than adding people to a Google+ circle, which is a built-in, not added-on, capability. In July, the San Jose Mercury News reported that Google claimed Google+ users are two to three times more likely to share privately with one of their circles than to post publicly.

Google+'s circles give users granular control over who their posts are shared with in a drag-and-drop interface. |

But Halavais said he remains cautiously optimistic about the future of the social network. If Google adds the features he wants, Halavais said, he'll integrate Google+ "heavily" in his courses.

"The possibility of easily enabling talk within a group, along with video chat and sharing Google Docs and Calendar is a killer combination for learning management," he said. "I'd say it's an obvious next step for Google+, but after earlier forays into social networking, I'm well aware that Google doesn't always take the obvious next step."

Halavais is no doubt referring to Google's Wave and Buzz projects. Introduced at the 2009 Google I/O Conference in San Francisco, Google Wave was billed as a real-time, shared communications stream that could include text, photos, videos, and maps, to which all participants have access. A Wave Web page could include tweets, Facebook messages, IMs, email, and a range of input from basic collaboration tools. Google stopped development of Wave about a year later, but handed it off to The Apache Software Foundation, where it lives on as the open-source Apache Wave project.

Google Buzz, the company's social networking and messaging service, launched a year later, generated widespread criticism over privacy issues. The United States Federal Trade Commission charged that Google used information collected from Gmail users to generate and populate the Buzz social network. The network was also criticized for automatically enrolling users in some features even when they opted out, and for an auto-follow option that added Gmail users’ most-emailed contacts as publicly visible friends on the network.

Google's track record is one reason Lynne Schrum, professor and coordinator of elementary and secondary education at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA, has adopted a wait-and-see attitude toward Google+.

"I use all other types of social media, but have held off on this so far," she said. "I'm staying away until I know how the information is going to be used and by whom. [For now] I won't answer or accept any of the invitations I get."

Schrum also argued that, because most universities use an LMS, such as Blackboard, "which has all the same features," there's unlikely to be a higher-ed rush to Google+.

And yet, Jeremy Littau, assistant professor of journalism and communication at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, PA, has encouraged his colleagues to jump into Google+ with both feet. In his July 7 blog post, entitled "Why Lehigh (and every other) University needs to be on Gplus. Now," Littau argued that Google+ "is going to change education."

"Already I can see Plus having a bunch of advantages over Blackboard or the Moodle learning system we use here," Littau wrote. "About the only advantage those products have is the grade book. Every other interactive tool those offer is inferior to what we have on Plus right now. Facebook has some great collaborative tools, but the privacy interface is so clunky that I rarely used the tools in classes for fear of being seen as infringing on their personal space. Circles changes everything. We'll be using GPlus in my multimedia courses as perhaps the most essential course-management tool."

Everyone interested in Google+ should keep in mind that these are early days, said Google spokesperson Iska Hain. "We're still in a limited field trial, and this is just the beginning," she said in an email. "But obviously Google+ has some really interesting features for educational purposes, including circles and hangouts."