Networking | Feature

iOS 7 Release Caused Huge Traffic Spike on Campus Networks

As thousands of students updated their Apple devices to iOS 7 last month, some wireless networks struggled to handle the traffic surge, while others were smooth sailing.

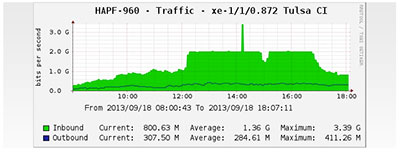

IOS 7 downloads caused traffic on the University of Arkansas' regional Arkansas Research and Education Optical Network connection to spike from 1.4 Gb/s to 6 Gb/s. |

On Wednesday, Sept. 18, many network administrators at campuses across the country were caught off guard as Apple released iOS 7 and thousands of students began to download it--and wireless networks saw huge spikes in traffic. Network World reported that some locations experienced wireless network traffic surging five times above normal levels.

Student newspapers at several universities reported outages or slowdowns of campus networks. For instance, Ohio University's Post reported an outage that affected internet access across several campuses, which university officials later confirmed was caused by the iOS 7 upgrade. And according to the University of Texas-Pan American newspaper, an e-mail from IT blamed an outage on "network saturation," with a follow-up message attributing the saturation to the iOS release.

Universities lucky enough to have upgraded their network capacity over the past few years were somewhat alarmed by the spike in demand, but survived it unscathed. "When you read about campuses that had trouble during the iOS 7 release--a few years ago that would have been us," says David Bruce, associate CIO for campus networks at the University of Arkansas. In 2007, he adds, the university had only a 150-megabit pipe that was regularly filled to capacity. But the campus network has since been upgraded to provide a 2 Gb/s pipe, and a regional network connection provides even more flexibility.

Yet when the spike hit, the network team at Arkansas wasn't prepared. "We were surprised at first because we didn't know what was causing it," Bruce admits. "We saw it was all coming from our wireless network. Your first thought is that it is either something malicious or something misconfigured. But one of our engineers said, 'Oh, that must be iOS 7,' and he was right."

Bruce says that as the cost of commodity internet has declined, Arkansas' strategy has been to buy enough that all its users can have a good experience and the university has a little headroom left for spikes. Today, its typical daily peak usage is around 1.4 Gb and it has 2 Gb of capacity. Additionally, the regional Arkansas Research and Education Optical Network (ARE-ON) has an Akamai content delivery server attached that Arkansas can access without using its commodity internet, and research traffic is able to go out via Internet2.

"During the iOS 7 traffic spike, the connection to the Akamai server on our regional network (a 1 Gb connection), was completely maxed out," Bruce says. "The regional network lifted the internet cap to see just how high it would go, the thought being that if it spiked up to 2.5 or 3 Gb, we could just let that go for a while--but the spike went all the way up to 6 Gb before they put the cap back on."

Another university that benefitted from a recent network upgrade was the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga. In a blog post, Christopher Howard, a senior network engineer, noted that there are 5,622 iPhones, 2,077 iPads, and 431 iPods registered on campus. His office tracked all four of UTC's internet connections in real time. The bulk of downloads on Sept. 18 came from EPB, its local ISP. On a normal day, UTC usually peaks around 300 Mbps (30 percent of the EPB connection's 1 Gb/s capacity) for that one connection alone. "However, when iOS 7 was released we spiked that connection up to around 950 Mbps (95 percent)," he wrote, noting that made it by far the largest internet traffic day in UTC's history.

While many universities had to throttle download speeds just to keep their networks from collapsing, Howard pointed out, UTC was able to reach this kind of speed because of some much-needed upgrades that were made in the recent past. "We were able to let it run untouched and most likely no one even noticed," he wrote.

At 600-student Sweet Briar College in Virginia, the iOS 7 update was very noticeable, but the campus network was able to handle it, says Aaron Mahler, director of network services. "Usually Netflix dominates as a network traffic source, but for that day Apple dethroned it," he says. Mahler says Sweet Briar has been expanding the amount of bandwidth it purchases, and he uses network controls to put a cap on wireless network speeds, although most users wouldn't notice it. He received no complaints about students unable to complete the download. "Although we do have a lot of iOS users, I don't think we are large enough to have the huge bandwidth spikes some larger universities experienced."

In a recent column, Kurt Marko, a writer for Network Computing, suggested that campus network managers should treat this event as a wake-up call. "It's a predictable consequence of the rapid, inexorable shift of software and content distribution from physical media or broadcast signals to the cloud," he wrote.

Marko quoted one of the contributors to the online North American Network Operators Group (NANOG), who said this incident should be a call to action. "Use it as an excuse to upgrade your pipes, talk Akamai or CDN [content delivery network] of choice into putting a cache on your network, or implement your own caching solution," the contributor suggested. Marko added that prioritizing traffic "will ensure that mission-critical applications get what they need and maybe even force a few iPhone users into waiting until they get home before firing up the update process."