Social Homework Platform Aims to Boost Student Engagement

Three Cal State Long Beach physics professors developed a new tool for making large lecture courses more interactive.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 02/25/15

Physics professors and Koondis developers (left to right): Zvonko Hlousek, Thomas Gredig and Galen Pickett

Figuring out how to keep STEM students in their disciplines has long stumped higher ed institutions. Just 43 percent of students who enter a STEM major in a four-year public college or university end up graduating with a STEM degree, according to a 2013 White House report. And the success rate is worse for students in community colleges.

The culprit may be freshman science courses, suggests research out of Harvard. Students' experiences in their first-year science courses are the "most influential" in their decisions to stick with a major or not, yet most students aren't happy with those courses. They cite a lack of "faculty-student interaction, 'coldness' of the classroom, lack of preparation and organization, and dullness of presentations" as proof that they're receiving "poor teaching."

These kinds of problems drove three physics professors at California State University, Long Beach to develop a new software tool for their own classes, which they are now marketing more broadly through a start-up company. Koondis, as it's called, works in traditional large introductory lecture classrooms, blended classes and fully online courses that often are filled with students enrolled from various disciplines who are required to be there for their majors.

Described as a "social homework system," a "discussion forum that puts students in small groups" and even a replacement for the campus learning management system, Koondis is showing great promise as a pill for student satisfaction.

The Problems Koondis Tackles

Thomas Gredig noticed that when students in his physics classes took their finals, some obviously hadn't learned certain concepts. But since it was final exam time, it was too late to remedy anything. He found that homework assignments in the university's LMS weren't supplying enough assessment data for him to know that a given student might be struggling.

Galen Pickett was frustrated that students had to wait until they were involved in a research project — not typically part of a first-year curriculum, let alone the first semester — to get involved in experiments where the answer wasn't already known.

Zvonko Hlousek wanted an "assistant" that could help his students "build the right work ethic for the process of learning," because he knew those students would be the ones who performed the best. Plus, he was tired of having to use standardized textbooks, calling them "big behemoths" that are "difficult to read" and don't encourage "good learning."

The three CSULB faculty members came together with the goal of developing an application that could put students into small groups to undertake projects and experiments, provide information to help determine when a student was struggling, and automate the process of grading student participation.

Managing the Team

Koondis (named for an Estonian word that means "select team") was cobbled together from open source software. The platform evolved out of research the three professors had done on leveraging social networking techniques students already gravitated to — Facebook, Instagram and Twitter — to support the study of highly complex material.

The software allows instructors to group students, assign each student a role in the group and map that role to specific tasks that lead to more effective problem solving. Roles encompass project director, investigator, executive and skeptics (held by two members), the same parts a science team might include in doing research. The software rotates students' roles from one assignment to another so that eventually every student participates multiple times in every role.

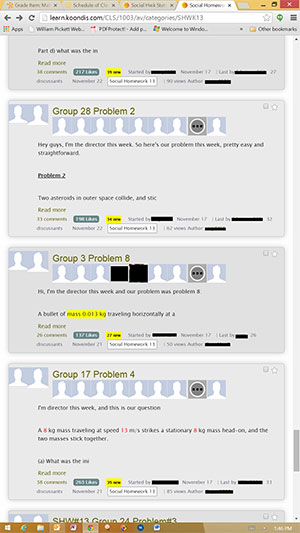

The Koondis student view

In classes led by Pickett, for example, each group is assigned a problem from the current week's problem set, and the members work within the built-in discussion board to complete their roles with the help of their teammates. Every group can see the work of every other group. At the end of the week, the project director summarizes the groups' work and posts it in a showcase where everybody else in the class can review it and "like" or comment on it.

Tribal Tactics

The group aspect can't be underestimated. Like a gym buddy or weight loss team, people respond to that commitment and become "very protective" of their groups, Pickett noted.

The software makes new college students feel like they've found a tribe, according to the professors. "There's just a strongly qualitatively different experience for students walking into a 100-level class [during] their first semester on campus. There are four other people in that room who expect them to be there, who are waiting for them to contribute, and thanking them: 'I loved your comment last night. Thanks. That helped me do my homework,'" explained Pickett. "It's an overwhelming positive reinforcement that has really helped our retention of underrepresented students in these science, technology and engineering fields."

The trio of physics professors/developers acknowledged that this same kind of approach could be handled by an LMS, but it would be tedious work to have to track roles and group interactions. Because the work is being done within teams and it's all online and publicly viewable within the class, team members and other groups provide the kind of feedback that might normally originate from the instructor. The idea is that Koondis eliminates the need for teachers to read all of the posts. The program even counts posts for the instructor for grading purposes, and alerts the faculty member to do follow-up when a student isn't participating.

Learning to Be Wrong Well

Koondis is also effective at educating students in an area that's difficult to teach through books: the scientific approach. "In the old times, a student would submit an answer, and he or she would basically be downgraded for submitting an incorrect answer," said Hlousek. With Koondis, the student is "rewarded" with positive reinforcement for posting, because it allows the community to consider the merits of whatever the student has postulated. "Being able to falsify any kind of statement is the staple of science. It is that aspect that Koondis brings into the learning."

As Pickett noted, "Posting something that's not correct is considered positive or valuable because other students can see that alternative perspective, and it creates an opportunity for them to instruct their peers, allowing [them] to reply to a question and say, 'Are those units correct?' or ask questions. Students didn't have that before."

"Traditionally, the teacher said what was right and wrong," added Gredig. "It was the student's job to get the right stuff. We are [in] the 21st century. Students need other qualifications. Koondis is the ideal platform to enable students to judge and discuss whether something is right or wrong."

Forging a Bond Between Student and School

To gauge the impact of Koondis on student attitudes in what is typically their very first physics class, PHYS 151 (a common course offered at multiple institutions), Pickett and his colleagues ran a survey among the 180 people in the class. Typically, when students are asked for their reactions to statements such as "Helped me feel connected to peers" and "Encouraged me to spend more time," the responses on a Likert scale would average about one or two. By those measures, Koondis was a wild success. "Helped me feel connected to peers" came in at 3.52; "Encouraged me to spend more time" was 3.74; and "Helpful for problem-solving" was a remarkable 4.24.

"A typical 100-level science and engineering class is not designed to pull people into the university and have them feel connected to a community," Pickett pointed out. With Koondis, "Now it is."

Forging that bond between the student and the university right from the get-go, he added, is helping to "keep people in these degree programs who could get discouraged and move elsewhere in the university."

To push the project further even as classroom research was going on, Hlousek and Gredig formed a company to service the application and develop it further. Pickett joined as head of analytics. (The university and the company negotiated an agreement on intellectual property related to Koondis, and EduDotOnLine was born.)

What the fledgling company has discovered is that Koondis is "subject agnostic." "While we used it in the sciences, the system can be used in any subject," said Hlousek.

The Power of a Social Platform

The company founders insist that the setup of Koondis is as straightforward as entering the list of students and deciding what the tasks will be for the given roles. Because they've already mastered a "workflow" for the use of the software in their own classes, however, the instructors make themselves available through a "concierge" service to work with faculty members one-on-one, in a train-the-trainer model.

Pricing is set at $35 per student per semester, which Hlousek considers a bargain compared to the typical physics content that includes online components provided by mainstream publishers. "Their systems actually carry quite a larger price and deliver this old-fashioned experience that we have discovered is not conducive to learning," he said.

Several universities in Minnesota and California are already testing out the application, and Hlousek anticipates more interest as soon as a redesign of Koondis is done to convert it into a cloud-based software-as-a-service offering.

"As we go into the future, content that's the equivalent of textbooks will be available on the Internet. What students really need is a platform where they can interact — a social platform," asserted Gredig. "Koondis has those social aspects integrated. Students can 'like' discussions. They can see what's trending up. They can ask questions. They can thank someone for giving an answer. They can share something they've written. They can snap a picture and post it like Instagram. The social platforms are more effective to the students, to the instructors who are teaching them, and to the institution to retain and make learning available to all students."