A Return to Best Practices for Teaching Online

A Q&A with Judith Boettcher

Technology advancements have made online learning environments seamless, and our daily and nearly continuous exposure to online modes for communication in almost all areas of our lives seems to have made almost everyone comfortable working online. But is the distinction between online learning and campus-based instruction disappearing? And are all teaching faculty necessarily prepared to teach online?

The lines between online learning and campus-based courses might appear to be blurring over time, but it's important to realize that there are, and always will be, differences. Asking faculty to move their courses online may be deceptively simple. That's why co-authors Judith Boettcher and Rita-Marie Conrad have refined a list of 14 best practices based on core learning principles to help faculty succeed in creating effective online courses.

Here, we've asked Designing for Learning consultant and author Judith V. Boettcher about the development of these best practices and their impact for online learning. [The list of 14 best practices is included at the end of this article.]

Mary Grush: Earlier this year, you published an update of your book, The Online Teaching Survival Guide (second edition, Jossey-Bass 2016). In chapter three, "Best Practices for Teaching Online: Ten Plus Four," you and your co-author Rita-Marie Conrad provide a list of 14 best practices for teaching online. How can these best practices help faculty? Why "ten plus four"?

Judith Boettcher: Let's begin with how this list came about. Over many years of working with faculty, we found out — and I guess it's really no surprise — that when faculty are first asked to teach online, most do not have a lot of time to prepare. They are seldom given much coaching, mentoring, or support — often they are just kind of thrown into it, or it may have been that in a weak moment they said, "Okay, I’ll do it."

Faced with faculty panic over teaching online, we created, for the first edition of the book (published back in 2010), a set of 10 best practices for faculty who needed a fast, quick "how to teach online" based on a companion set of core learning principles. We devote chapter 3 in the book to best practices, so that if you only have time to read one chapter before teaching online, you can follow and apply these best practices. You and your students will not only survive through the first online course you teach — everyone will probably enjoy it, which generally results in good course evaluations as well.

Grush: Are these best practices only for first-time online instructors, then?

Boettcher: No, they are for anyone who teaches in online or blended environments. I like to encourage faculty to refer back to them frequently. If someone is thinking about online learning or learning in close-to-online-experiences, these best practices can be a quick confidence booster. They are a great set of best practices — based on learning principles — that inform and guide course design and teaching.

Grush: So you also linked these best practices to broader learning principles?

Boettcher: Yes. And thanks for highlighting that, because that's core to the effectiveness of the best practices. In the second chapter, "Pedagogical Principles for Effective Teaching and Learning: Ten Core Learning Principles," we describe 10 core learning principles that are the foundational thinking for the best practices. This chapter is especially valued by faculty, because they rarely get a chance to revisit teaching and learning pedagogy before launching an online course.

Grush: Then for the second edition, published this year, you added to your list of best practices — there are now 14. Why did you expand the list?

Boettcher: Over the years, as my colleagues and I worked with faculty teaching online, we discovered that beyond the teaching online questions, faculty were very concerned about how to do assessment well online. We found ourselves supporting faculty in the development of assessment plans and recommending continuous, ongoing assessment strategies — including peer review strategies and a focus on creating as a way of assessing. Out of those discussions, we developed the four additional best practices for the revised book edition, and they are described in the updated chapter three.

Grush: How do the 14 best practices impact the work of online faculty most?

Boettcher: First of all, the best practices will help faculty develop confidence — particularly those faculty new to online teaching. Even if they don't have any experience in teaching online, if they apply the best practices, they will probably do well. And of course, when they do teach online, they acquire expertise and curiosity about the new environment that takes them beyond their initial application of this foundational set of best practices.

Another significant impact is that, as faculty develop more confidence in implementing the best practices, students generally become more satisfied with the learning experience. For example, in the best practices, we talk about the idea of faculty being present in a course. This best practice applies the research from the Community of Inquiry model and the three presences — social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence. We find that when first teaching online, faculty's approach is a mindset of the campus-based experience, where they will often say something like, "We'll talk about x-y-z on Tuesday or during the next class…" But, today's online students like to see, hear, and feel that faculty are present virtually every day of the week in some way. So developing almost daily presence online by staying in touch with students and being responsive to postings and queries in a timely way has terrific impact and is absolutely the most important of the best practices. Faculty are perceived positively even in the face of other faults if they practice their social, teaching, and cognitive presence well.

Recently — with recent being in the past ten years — we've seen the push toward more accountability and measurement in higher education. I do believe that the 14 best practices can guide the development of tools and policies that can effectively support meaningful accountability to learners. The best practices also suggest ways for measuring how students themselves engage and take responsibility for their own learning. This in turn impacts learning quality and the measurement of successful learning.

These best practices can also move us toward more meaningful, satisfactory, and effective learning overall. Why? Because they support the development of coaching and mentoring relationships that in turn make possible more customized and personalized learning.

One of the best practices (#9) highlights the benefits of combining core concept learning with personalized learning. For example, we know that for students to become excited about learning, they need to feel that it will really make a difference in their lives. If we apply the best practices, students will be motivated, because the best practices encourage us to ask the following questions: "What in fact are students going to be able to know, what are they going to be able to do, and how are they going to be different as a result of this course?" And we ask the students themselves to think very actively about what it is they want to learn from their investments of time and money in the course. When we combine the core concepts from the course with personalized learning, students learn the core concepts, but they apply those concepts in an environment and context that is meaningful to them.

Yet another impact of the best practices is that we get a more intuitive feel for great course design that incorporates assessment. We want to connect the course content rigorously to what we identify as core content and learning outcomes. And the best kind of learning happens when we can integrate the learning experiences with the gathering of evidence. Sometimes the "project" of what students create in a course becomes the learning outcome — much as a piece of pottery we've made provides evidence about what we have learned about pottery making. The learning experience itself becomes the outcome; the creation becomes the assessment.

Some of the best practices suggest strategies that can extend your thinking for your traditional, campus-based courses. In traditional courses, we often give problems for students to solve, but they are problems for which the solution is already known. It's much more exciting for students to take on problems and cases for which we don't have a solution or for which there might be many alternative solutions. Doing this may take them beyond what they are "supposed to know," but that's really the point — you give them problems and challenge them to find solutions that are not immediately obvious. This is the kind of learning that incites curiosity and develops long-lasting skills.

There are many — you might even say endless — impacts of following the best practices, but those I've just mentioned are good examples I think, that address current issues for online teaching.

Grush: How does the online environment uniquely support personalized learning as you've just outlined it in the best practices?

Boettcher: Personalized learning means that while all students master core concepts, students ideally practice increasingly difficult use of those core concepts in contexts and settings desired by individual students. For example, in a leadership course, students who are interested in leading international efforts abroad or in various business settings use materials and cases specific to those contexts. In other words, they are practicing and applying knowledge and problem solving in their own preferred context. Then students bring back to the course community their experiences from these different contexts. A course is enriched with these stories from students that turn into learning experiences for their peers online as well. Taking that a step further, because you are online, you have the option also to broaden the audience the student has for their work — to others on campus or possibly at other institutions, or maybe even more widely or to the world.

Grush: Do you have a model in the book that takes an even broader look at the role of the learner?

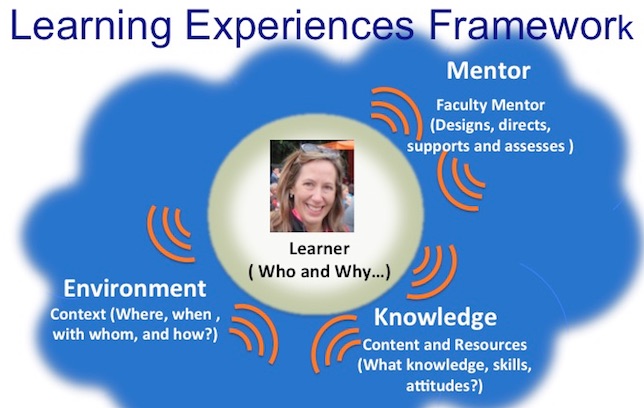

Boettcher: The Learning Experiences Framework graphic (source: The Online Teaching Survival Guide, Boettcher and Conrad, second edition, Jossey-Bass 2016, p. 27) captures all the elements of any structured teaching and learning experience. The learner is at the center, guided and mentored by the faculty, in the knowledge, skill, and perspective to be acquired and the environment where the learning is taking place and when and with whom. I like to note that just as our entire physical universe is composed of the four elements of air, fire, water, and earth, so too teaching and learning is comprised of only four elements.

Grush: If we think at this level as we design and create online courses, will we be able to address the expectations we see coming to us from the accountability and assessment movement?

Boettcher: I would like to see expanded interest and focus on designing courses with the close linkage of core concepts to learning outcomes. To do this, I believe, we really need to step up to much more effective use of rubrics. Rubrics can define intellectual outcomes in several key areas, such as critical thinking, for example. The VALUE rubric project of AAC&U provides a set of rubrics for many transferable skills such as problem-solving and teamwork. The rubrics are extremely useful as models and starting points. So, as we take our best practices and really focus on core concepts and link them to learning outcomes, we would ideally use rubrics that define the outcomes and abilities that we want our students to have. That's how it will all come together to address this need for assessment and accountability, long term.

Grush: Still, I have to ask, how might we eventually reach the cultures of diverse institutions, say, nationally?

Boettcher: It's hard to impact the world! We are a ways away from critical mass in achieving accountability broadly, even given the many projects underway by different organizations. The effort for accountability is complex, but very important. It's worth our time, and I hope more institutions will invest in at least helping their faculty create good learning designs.

Grush: It sounds like good learning design is still at the heart of any great online course.

Boettcher: Yes, I believe that great course design is at the core of creating great online learning experiences. We need to ensure that the desired learning outcomes, the course experiences, and the ways we gather evidences of learning are all congruent, one with the other. Course experiences should help students develop the knowledge and expertise that they desire, and the evidences of learning we require of students should be meaningful and purposeful and where possible, personalized and customized.

This may seem like a lot to consider, but you have to start somewhere, and our 14 best practices based on good pedagogy [listed below] have and will be very helpful and productive for online faculty. The 14 best practices in combination with the 10 core learning principles together provide a foundation that will take us a long way towards the achievement of all these very ambitious goals.

Best Practices for Teaching Online

From The Online Teaching Survival Guide, Boettcher and Conrad (second edition, Jossey-Bass 2016), p. 45

[1] Be present at the course site.

[2] Create a supportive online course community.

[3] Develop a set of explicit expectations for your learners and yourself as to how you will communicate and how much time students should be working on the course each week.

[4] Use a variety of large group, small group, and individual work experiences.

[5] Use synchronous and asynchronous activities.

[6] Ask for informal feedback early in the term.

[7] Prepare discussion posts that invite responses, questions, discussions, and reflections.

[8] Search out and use content resources that are available in digital format.

[9] Combine core concept learning with customized and personalized learning.

[10] Plan a good closing and wrap activity for the course.

[11] Assess as you go by gathering evidences of learning.

[12] Rigorously connect content to core concepts and learning outcomes.

[13] Develop and use a content frame for your course.

[14] Design experiences to help learners make progress on their novice-to-expert journey.

[Editor's note: Each best practice is expanded and described in detail in the book.]