2016 IT Salary and Job Satisfaction Survey Results

Our latest survey of higher education IT professionals showed earnings that are mostly looking up in a segment beset by lingering frustrations that probably won’t go away any time soon.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 02/02/17

IT people in higher education sit at an interesting juncture. They continue dedicating themselves to support and delivery of services that have seemingly always been there — e-mail, websites, wireless. Yet, they also keep one hand firmly on new technologies that are enabling innovations in the learning business. That's a tough combination of responsibilities to juggle — yet, from what we've seen, most do it well.

What's that worth? In this year's Campus Technology salary survey, the average salary across all types of institutions and every kind of IT role imaginable was $77,808. The highest salary reported by a respondent was $224,000, made by a chief technology officer in California. The lowest was $22,000, earned by a help desk staffer in Missouri. The median (that number that falls exactly between the highest salary and the lowest one) was $71,173.

With those kinds of extremes, pay is a sore spot. However, it appears that other aspects of the job help balance out the grief (as you'll see shortly).

The individuals who choose to work in this industry come across as both dedicated and disgruntled. We heard from people all over the country who told us, "I really enjoy working in IT in higher education," as one systems administrator in Michigan did, or "This is an exciting time for e-learning and for technology in higher education," as an IT manager in Texas declared. We also heard from less positive folks, such as the systems administrator in Washington who wailed, "Rising needs and costs, lower budget," and the technician in Florida who murmured, "Slow to change, slow to meet client change requests, and slow to realize potential in new technologies."

Overall, respondents paint a picture of an occupation that's beset by frustration with top leadership and shrinking IT budgets but softened by co-workers they enjoy, hours they appreciate and benefits that can't be beat.

Average Salaries

The average salary this year for those working in IT organizations within public institutions was $74,390, within a few hundred dollars of last year's average of $74,021. The median was $69,400, a bit higher than last year's $66,000. For people at private not-for-profit schools, the average salary was $83,441, considerably higher than last year's average of $75,771. The median there was $75,000.

At the top end of the salary range are the C titles: chief information officer, chief technology officer and chief security officer. The average among those roles at public universities and colleges was $113,494, and the median salary was $110,000. That's considerably less than what was earned at private not-for-profits by individuals with comparable titles, where the average was a whopping $165,657 and the median was an even higher $174,000.

The average salary for people holding director-level titles in public institutions dipped from last year's $105,090 to this year's $96,400. At not-for-profits this year's average salary for IT directors hovered at $96,000, within a tenth of a percent of last year's $96,098.

The lowest average salary earned by IT workers went to those involved in providing help desk or tech support. At publics, the average salary for help desk jobs was $57,503, an increase from last year's $49,141. At not-for-profits it was $46,400, a drop from last year's $52,636.

In between the CIO and help desk are a multitude of other jobs, with their own average salaries. Figure 3 shares details for those titles that had sufficient response for us to be confident in the numbers.

No matter what the title, however, some respondents lamented what they perceived as overall low salaries in the education segment. "Depressing that I make 60 percent of what colleagues in similar for-profit organizations make," said a systems administrator at a not-for-profit in Massachusetts. "Also sad that I have no hope of promotion or significant raise or even job title change anytime in the foreseeable future."

A business intelligence analyst at a Washington university observed that salaries within public institutions "are tied to classifications and schedules — very rigid system."

Another respondent railed against the gender gap in salaries. Although the Campus Technology survey doesn't ask about gender, a technical support professional at a not-for-profit in Pennsylvania suspects there was "still a tremendous inconsistency in salary for women vs. men in the same job role, especially in education."

Higher education IT "is plagued" with income inequality, added a systems analyst at a two-year public college in North Carolina, and that's having an impact on the level of service that can be delivered. "At my location many staff members are being paid in excess of $10k less than market value for the jobs that they perform. This is slightly offset by a positive culture and environment, but it keeps us from maintaining top-tier talent and provides a revolving-door effect."

Forecasting Raises in 2017

The expectations for getting a salary bump in the new year depend on whether you work in a public institution or a private college. At the publics, only four in 10 people (42 percent) said they see raises on their horizons. However, at private not-for-profits, which have a bit more latitude, that's reversed: Six in 10 (60 percent) reported that they do expect to receive raises.

Promotions are expected to be few and far between. Only 8 percent of respondents within public and private not-for-profit institutions predicted that they would officially receive new titles in the coming year. However, that doesn't mean they won't be gaining more responsibilities or working harder.

"Challenging to stay relevant, obtain new skills while still responsible for supporting existing applications," complained one tech support professional at a four-year public school in West Virginia. "Usage increases and systems [are] more complex, but support staff numbers stay fixed."

"Condensing of job duties and limited budgets increase my workload. I spend two to three hours after my children [go] to bed to keep up with my workload," grumbled a trainer at a four-year public university in New Jersey.

Job Experience and Duration

A solid three-quarters of respondents have been in IT for more than 10 years, whether at publics or not-for-profits, compared to 72 percent in 2015. A slight majority (51 percent) have been at their current institutions for longer than 10 years at public institutions and not-for-profits.

Perhaps it's a salary that won't budge or a lack of promotional opportunities, but a hefty number of IT people are looking for their next opportunity. A full 20 percent of individuals employed at the public schools and the private not-for-profits asserted that they expect to leave their current employer for a new position elsewhere in the coming year.

These kinds of turnover rates won't surprise some readers. "IT in higher ed is often a stepping stone to other work outside the educational sector," suggested one IT manager at a private not-for-profit in Texas. "We've probably turned over 60 percent, with most people moving on to corporate work."

Another respondent, an IT director at a not-for-profit in Vermont, noted that it's "too hard to hire good help. Can't pay them or retain them."

Outsourcing Is Entrenched

A new question on this year's survey asked people to tell us about the likelihood of outsourcing in their IT organizations. All types of schools reported using outsourcing to some extent, but it's more common at private for-profits; 41 percent said their operations already or expect to hire outside service providers to deliver IT functionality. At public institutions, only 17 percent reported the same.

And, as one might expect, the topic generated a number of perspectives. Outsourcing is viewed by some as a "dangerous path for an institution to take," as an IT manager at a public two-year college in Arizona expressed it.

"People who outsource badly will re-learn the lessons already learned by many others before them," warned another IT manager, this one working at a private not-for-profit in Missouri.

Other respondents were more circumspect, neither positive nor negative. "As everywhere else, there are cyclic fashions in outsourcing and in-house efforts," explained an IT manager at another private not-for-profit in Missouri. "Each has advantages; either can be done well or poorly."

An IT professional handling learning management system administration in Colorado at a public four-year university pointed out that outsourcing can also mean taking applications to the cloud, "which removes some of the pain of server maintenance from us, but requires us to change how we view and apply security."

That kind of shifting around of priorities can prove a boon, added an IT director at a public institution in Oklahoma: "Outsourcing storage and other services frees up staff to pursue impact projects, which in turn leads to feeling invested and responsible for positive change on campus."

Positive Outlook and Job Satisfaction

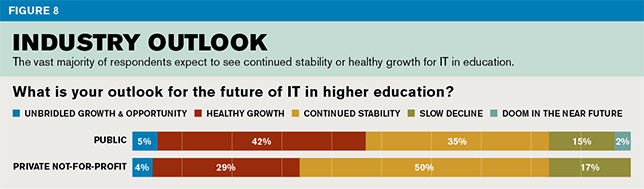

When asked to share their outlook for the future of IT in higher education, most respondents expected more of the same — whatever that happens to be. Those working for public institutions were slightly more optimistic; 42 percent forecasted "healthy growth," compared to 35 percent who expected continued stability. They were also the most pessimistic; 2 percent foresaw "doom in the near future," compared to 0 percent of privates predicting that. Yet the shadows looked longer at the private not-for-profits; only 29 percent expected healthy growth; half anticipated continued stability.

For the most part, survey participants are happy with their jobs. More than three-quarters (78 percent) said they were overall satisfied or very satisfied. The three most satisfactory aspects of their positions within higher ed were the hours they work (82 percent of respondents said they were satisfied or very satisfied with that); the co-workers they have (81 percent); and the benefits they receive (80 percent).

Physical comfort and equipment were also high in the rankings; 73 and 72 percent of people reported satisfaction in those areas, respectively.

Seventy-one percent of respondents said they were happy with their supervisors and 69 percent expressed contentment with their commutes.

Top Complaints

The three areas on the job that bothered respondents last year are the same ones that bug them this year: salary, upper management and department budget. A third of survey participants (31 percent) said they were either unsatisfied or very unsatisfied with their pay. Even more (34 percent) said the same about their IT budgets. A quarter of people (27 percent) reported unhappiness with "top brass."

Dissatisfaction with budget and clueless administration was also the primary theme for many of the comments people contributed in their survey responses. "IT is continually called to cover more areas and to do more without any increases to budgets," bemoaned an IT director at a private not-for-profit in New York.

The CIO for a public two-year institution in Minnesota agreed: "Budgets continue to decline to the point where we struggle to refresh our technology and our staff."

"Overall, poorly treated, underappreciated, underpaid, and not enough professional training, respect or any concern at all for employee morale," summarized an IT manager with a public four-year institution in Ohio.

The biggest "disconnect," added an IT manager from a private for-profit institution in Massachusetts, "is that clients (and campus leadership) don't always have a great understanding of the complexity of IT, so it is hard to get them to spend what is needed to fully staff [or] support it the way it really should be."

"Higher education needs to control spending in only one area to solve its budget woes: top executive compensation," suggested a project manager at a four-year public institution in New Mexico.

"Sadly, senior leadership on my campus places no value on information technology, choosing instead to view it as a necessary evil," concluded an IT director at a public institution in Oklahoma.

What the Near Future Could Bring

As one survey respondent, a systems administrator in New York, put it, the "new and shiny" draws most of the attention in the tech industry, while operational support is often taken "for granted." Such is the lot of the IT professional working in many industries. The difference with higher ed, however, is that there's so much more at stake than mere profit.

Technology not only sustains the back-office business of the university or college, but it also serves as a beacon for students, drawing them to the institution in the first place, providing new mechanisms to keep them engaged, and helping them succeed with their learning.

Yes, the job is becoming more complex and more important. "We are no longer just maintaining the nuts and bolts at all times," noted an instructional technology and design manager at a four-year public school in Maryland. "So many services and projects require a broad understanding of the institution, integration with several units and a lot more project planning and data analysis. IT is the underpinning of so much of the operation and growth of the institution."

Yes, as another instructional technologist at a two-year community college in California observed, "IT is underestimated, underfunded and overlooked." And yes, it's led by a leadership that may be good or may be bad, she added. But ultimately technology makes up "the future of every occupation, every classroom and every part of our lives."

Without the work you do, without the work done by IT professionals in every school across the country, higher education would be a very different experience today.

A tech support specialist at a tiny school in Michigan understands this pivotal role that tech plays, and this person is nowhere close to giving up fulfilling the role that IT can play in the learning business. "We are a small college with less than 300 students, so technology is not like Michigan State; but we do try to give students the best we can. Could it be better? Sure, and maybe someday it will be. But I feel that technology will always have its place in education."