4 Ways to Use Social Media for Learning

These four uses for social media in STEM courses focus on deepening student learning through better communication.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 05/18/16

Social media continues to offer great promise for enhancing learning in the classroom. Much of the usage in college and university courses emphasizes collaborative activities, such as sharing ideas and building community — the social half of the term. But sites like Wikipedia, Twitter and YouTube are useful platforms for the media side too, enhancing communication and content delivery. Here, we look at how educators in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) are tapping into both aspects of social media for learning. Of course, many of their methods can benefit students in any subject.

Science: Wikipedia for Graphic Communication

When Bruce Sharky, a professor at Louisiana State University's School of Landscape Architecture, incorporated Wikipedia into a graduate class, he sparked a track of coursework that is still fondly remembered by his former students. It started when Sharky happened to attend a meeting where representatives of Wikipedia were attempting to persuade faculty to get their students involved in improving the content quality on the site as part of a new grant program. His idea was to have students develop and add new graphic images.

The regional planning class he had in mind for the project was studying the coast of Louisiana. So Sharky developed a list of "about 15 or 16 subjects, such as global warming, ground subsidence, salt water intrusion [and] reduction of biodiversity," he recalled. The students could pick whatever topic they wanted, find articles related to it in Wikipedia and then develop a graphic that would explain the concepts or content in that particular article.

"The students liked doing it," said Sharky. "And they were quite blown away by the fact that they would put their graphic up for people to see and then they got comments from around the world: 'You could improve this by doing this.' 'This is wrong.' 'Change that.' They got feedback that they found phenomenal."

Along the way, the exercise also "improved the graphic communication of my students related to landscape architecture," he said.

He repeated the exercise the following year, but the students didn't seem nearly as excited. So a year later he partnered with a biology professor to bring two undergraduate classes together for collaborative work. In teams of two, the biology students would contribute to the text of Wikipedia articles while Sharky's students would create graphics for those same articles.

"That didn't work out very well," Sharky acknowledged. Students were challenged to meet because the schedules of the two classes were so different. "We tried it twice and we were just not happy."

While that spelled the end of the Wikipedia experiment, Sharky is considering bringing it back into his classes in the original format. The exercise forced his students to "learn how to read Wikipedia," he pointed out. "Particularly in the sciences, you realize just how rich those articles are, beyond just the words that you read. There are backups, references and things that can really help you explore the depth of the topic that you're looking at."

Technology: Social Programming for Persistence

A project underway since 2007 to improve retention in computer science programs recently took a new twist. Chris Hundhausen, a professor in the Washington State University School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, received National Science Foundation funding to develop a social media platform for the students in introductory computer science classes. The original thinking with the Online Studio-Based Learning Environment (OSBLE) was to create a way for students to participate in a community with shared programming activities; students would tackle their assignments within a special online environment occupied by other students as well as instructors and industry professionals. People could evaluate each other's coding efforts, answer questions and encourage persistence.

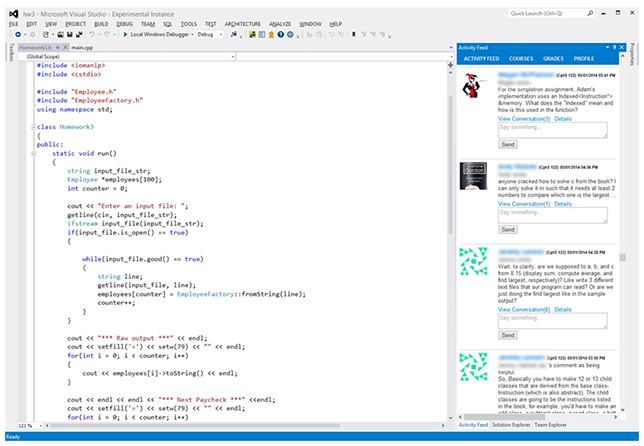

Now the project is releasing Online Studio-Based Integrated Development Environment (OBSIDE), a plug-in that provides similar functionality, but without the weight of the whole learning platform behind it. The extension works specifically with Microsoft Visual Studio to provide "social programming" features. "That plug-in brings into the programming environment a Facebook-style activity feed," explained Hundhausen. However, the overall goal is the same: "to make programming less isolating and more social using the same kinds of technologies students are using to socialize online." So far, he noted, OBSIDE has been used by 1,000 to 2,000 students at Washington State over the last four semesters.

The Online Studio-Based Integrated Development Environment socializes the programming experience with a Facebook-style activity feed.

Normally, a student would have to go into another system — a discussion forum, Facebook or something else — to ask questions online. "Our environment makes it really easy for students to ask those kinds of questions in the very context in which they arise," Hundhausen said. "We're erasing the barriers. It's making a huge difference. We have data to show that the participation in these conversations increases tremendously because of that integration with the programming environment." Students are asking a lot more questions, he said.

Hundhausen and doctoral student Adam Carter have found "a strong correlation between social behavior and course performance": Students who are more active socially do better in the course. The research project has collected evidence to show that the very act of students asking questions and getting answers and then reading the answers helps them "make quicker progress toward the solution."

OBSIDE is being released as an open source project. Already a university in Germany has undertaken the work of making a version of the plug-in available for Eclipse, an open source programming environment that may have more traction in higher ed introductory computer science courses than Visual Studio, Hundhausen suggested.

"Traditionally computer science has been seen as a discipline where students work in a very isolated manner, individually on problems. What we're trying to do is build this learning support community," said Hundhausen. "According to social scientists, the persistence factor happens through the friends that you have, that you're part of a community, that you're not in it alone. What is going to keep people in the discipline is that sense of community that could be built through this kind of technology."

Engineering: YouTube for Assessments

A lot of engineering coursework tends to be done on pen and paper, including the tests, according to Jeffrey Erochko, assistant professor in Carleton University's Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Oftentimes, during office hours, Erochko would hear from students that they'd done poorly on exams because they "blanked out or got stressed or didn't have enough time to finish it or forgot something." Yet, they could face him in his office and "at least explain the concept." He could see that they had some level of understanding about what was going on, "but they weren't able to demonstrate that at all on the test."

Because Erochko's classes tend to be on the large side — 150 or 180 students — it isn't possible for him "to sit down with every student and get an idea that they understand the content or not," he said. So he decided to try to replicate that experience online, asking students to create a minute-long video and post it to YouTube to demonstrate their understanding. "The idea was that it's a stand-in for oral assessment," he explained.

As he noted in a paper delivered at the 2015 Canadian Engineering Education Association Conference, "The short timeframe of the videos requires students to think critically about the concept and to explain it concisely." There was also the advantage that Erochko's teaching assistants could grade the videos "quickly, even in a large class," he pointed out.

During the semester, the video assessment is required twice. Students are given the choice of "opting out" of the activity; but they have to replace it with an in-person presentation given directly to Erochko in his office. In the three years that he has been running the alternate assessment, only one student has chosen to opt out for "philosophical" reasons.

Erochko chooses to use YouTube because "it's very convenient." Students aren't evaluated on the quality of the video; they can simply use a smartphone to capture the recording. And they don't even have to memorize what they're doing to say — they can simply read it. Nor are the videos expected to be made public. "I encourage the students to make their videos unlisted so that they will feel more comfortable creating their video without feeling that a lot of people will potentially watch it," he said.

This isn't the only use for YouTube that the Canadian professor has found. He has also set up his own channel, "The Civil Professor," where he posts examples for his students. "I basically go through sample questions related to the material, because I don't have as much time in class to cover as many examples as I'd like to."

Math: Twitter and Storify for Class Q&A

When students in James Anderson's courses have questions, they can raise their hands or take to Twitter. Anderson, a mathematics professor at the University of Southampton, began offering the Twitter option when he realized that some students weren't comfortable asking questions in a large group. Later, he added Storify to the mix as a way to maintain a record of those digital communications and included questions that were e-mailed to him as well.

"I realized that Twitter is not a permanent medium and that tweets disappear over the space of days or weeks," he explained. "Using the class Storify to answer e-mails from students was a natural extension of using Storify as a place to capture tweets, and to allow me to expand on responses to the tweets where appropriate. After all, a question that one student e-mails to me is a question that I'm sure other students have — and even if they don't, they should still be able to see the answer. The volume of e-mailed questions tends to pick up as we get close to exam time, and then I think it's very important to allow everyone to share in the answers."

Storify gives math students at the University of Southampton a place to ask questions without the pressure of speaking in front of a large class.

At the beginning of class, Anderson logs into Twitter and then during his lectures he attempts to respond to Twitter questions as soon as they come through. He said he was initially "concerned that the volume might get too large to be able to respond in real time, but in practice this has never been an issue." Sometimes, he added, he'll provide a short oral answer and then an expanded response in Storify.

"Like many others, I struggle to get real-time interaction with the students through the lecture, and I feel that being able to answer questions on the spot, whether oral questions or via Twitter, allows for the correction of misconceptions right away."

Anderson tends to see more Twitter action in his large first-year courses with 200 students, but more hand-raising in a final-year course with some 45 students. "My theory is that the final-year students are more confident in asking questions in class than the first-year students," he said. "The whole point was to provide an additional route for students to ask questions during lecture, and not to replace the oral questions."

While he's never done a formal evaluation of the use of Twitter and Storify, Anderson is confident he's on the right track. "The overall impact is best seen through the number of views and the number of questions asked, either by e-mail or by Twitter," he noted. But he calls it very much a work in progress. "I'm sure, for instance, there are ways of using Twitter differently and more actively, to engage with the students. And Storify — as good a place as it is for capturing tweets and e-mails and disseminating answers and additional commentary to all of the students in the class — is not an interactive discussion forum. But it's good for what I'm using it for."