Student at Risk: Now What?

Retention technology has revolutionized the way schools identify struggling students and manage the advising process — but the hard part is what happens after a student is flagged "at risk." Two institutions share how they have fine-tuned their intervention strategies.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 06/29/16

It used to be that Ramapo College of New Jersey instructors would be asked by myriad departments — athletics, specialized services and various financial aid offices — to fill out questionnaires giving feedback about the students in their classes. The goal was to find out how students were doing and whether they needed extra help. These surveys came in a multitude of formats and might, in some cases, ask about the same student who belonged to multiple programs. At best, said Chris Romano, vice president of enrollment management and student affairs, the response rate would be about 40 percent. The faculty feedback that did come in would really only go to whichever entity had done the requesting, and the faculty themselves would rarely hear back about what actions had been taken. The results would go into a black hole, never to be seen again.

Then in 2010, the 6,000-student college adopted Hobsons' Starfish Early Alert and Starfish Connect. The first is an alerting application and the second is a case management tool.

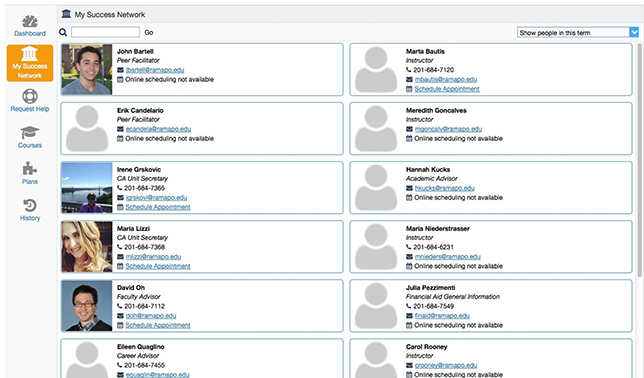

Now the school takes a more "holistic view of the student," noted Romano, where faculty or others can submit input and concerns about students within a screen or two, and in response, students can be connected to what the school calls a "success network" — a group of faculty, advisers and peer facilitators who provide academic guidance and help students navigate college life.

Muskegon Community College in Michigan follows a more straightforward approach for figuring out which students are at risk of failing classes or dropping out: The moment they enter college, they're considered at risk, explained John Selmon, vice president for student services and administration. His institution wants to make it "inescapable" that every single one of its 4,800 students gets the help he or she needs to succeed. Help can come in many forms: academic goal setting and planning, new student orientation, access to a college success course, developmental education, tutoring and supplemental instruction — all of which are high-impact educational practices recommended by the Center for Community College Student Engagement. Currently, the college has adopted seven of the 13 CCCSE practices; but in time it will put the remaining six in place as well.

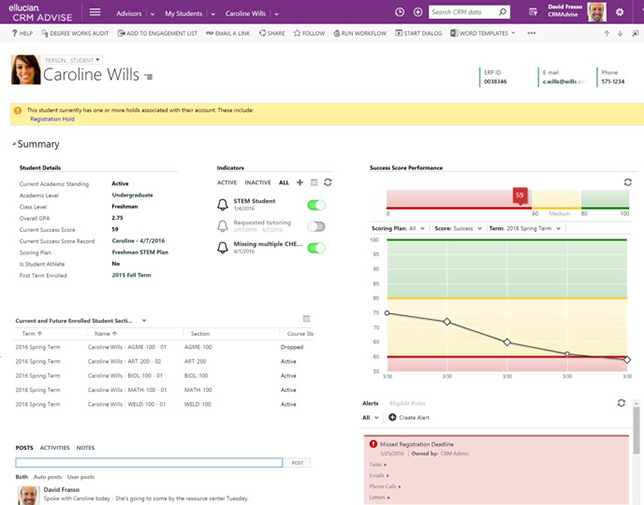

Last year, Muskegon adopted Ellucian CRM Advise, an application that provides an overall view of students, their risk levels and information about the intervention strategies that have been applied to mitigate the risks.

Ellucian CRM Advise

At both institutions, putting a retention system in place has been the first step toward boosting student success, but the real work begins after a student has been flagged as "at risk." Here's how two colleges currently meet the challenge.

Simplify the Response Process

At Ramapo, when a student hasn't paid a tuition bill on time or submitted financial aid paperwork by the deadline, Starfish Early Alert flags the lack of activity and notifies the student's "success network." A similar notification occurs when faculty members send up the alarm that assignments aren't being turned in or a student isn't showing up to class. The success network figures out who should get in touch with the student, and contact is made with specific directions. Though the directions vary, ultimately students head to a portal that lists the contact details for every instructor and office with which they have a connection, where they can engage in simple, fast communications — whether by sending an e-mail, making a call or setting up an appointment.

Ramapo's Student Success Network

"Students don't view us by what division or what VP we report to," said Romano. "They see us all as one college or one university. So we want to make sure we are providing them the opportunity, through technology, to interact with us as one place and not have them bouncing around."

Muskegon views the response effort as "working from the classroom out." As Selmon explained, "Students spend more time with our faculty than any other particular personnel here on campus." So when an instructor recognizes that a student probably needs tutoring, "They click a button, and the tutoring center gets that information. The tutoring center follows up on that person and gets them into tutoring."

Employ an Advisory Team

At both institutions, an advisory team helps monitor and continually improve retention processes. Muskegon's "academic care team" includes faculty, advisers, administrators and students. The Ramapo advisory board, which meets monthly, is chaired by the college's student success specialist — the campus expert on "all things Starfish" — and populated with at least one faculty representative from each academic school and a rep from the faculty assembly.

In both cases, the team tunes the student success process, talks about results, gets the faculty perspective and customizes the text of the automated messages sent out to students.

For example, when Ramapo first rolled out Starfish, the college used a "lot of flags," said Romano. "What we found is that at times, we were asking the same thing in three or four different ways using different phrases. We've condensed them into one flag that says, 'academically at risk.' We're trying to be more strategic about what we're asking faculty to tell us."

Focus on Closing the Gap

At Muskegon, when a faculty member has relayed a concern about a student, that "signal" is fed automatically to the care team, a group of people who do an assessment and decide what "point person" in the student's life should handle outreach. Once contact has been made, the point person adds a note to the system about what's coming up next — whether an appointment or some other action the student will take.

Both Muskegon and Ramapo have similar phrases they use to describe the full cycle of response for at-risk students. Muskegon calls it "closing the gap"; Ramapo refers to it as "closing the loop." But the point in either event is that the person who sends up the signal for help has a way of tracking the response. No longer is the finish disconnected from the starting line. Faculty or others with access to the system can find out what happened.

For example, Ramapo's athletic department reports to Romano. This traditionally high-risk population continually struggles to balance academics and athletics, he noted. So in the latest school year, he and his team set a goal of closing the loop related to athletics 100 percent of the time. If a faculty member raises a flag about an athlete, that alert goes to the coach and the athletic adviser, who have developed processes for the coach to respond about what is being done to support the student — whether extra tutoring, better class attendance or something else.

The athletic adviser is the gatekeeper to close those flags and report on what the coach is doing to make sure the athletes remain compliant with NCCA regulations, that they perform in class and that they are doing what they came to the college to do — "which is be successful academically," explained Romano. Even in the first year it has been applied, the use of the student alert system has had a "transformative impact on the relationship between athletics and academics at Ramapo," he said. And 100 percent of those open flags have been addressed.

While the results aren't all due to the technology, "technology does play an important part in terms of creating efficiency," observed Selmon. "If you can see on a screen where a person has a gap, and you can take that opportunity at that time to close that gap, it saves time and energy and everything else. It becomes very effective."