Babson College Finds Video Success on the Small Screen

By simplifying creation of videos with slides, audio, and other features, this business college has seen adoption of the practice taken up by nearly 60 percent of faculty. And now other departments are getting in on the act too.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 02/20/13

Faculty at Babson College in Babson Park, MA have been integrating video into their courses "strongly" since about 2003 or 2004. Back then, most of the videos followed one of two kinds of formats. The first were "talking PowerPoints," where a slide presentation would have audio added and the results would be encoded in multiple formats for different kinds of devices and posted to a server for student. Those would be created using products such as Adobe Captivate, Adobe Presenter, and TechSmith Camtasia. The second kind required an instructor to go into the college studio and work with instructional technology staff to create the video, including labor-intensive post-production using Adobe Premiere or Apple Final Cut Pro or similar products.

According to Eric Palson, director of instructional technology for the college's Curriculum Innovation and Technology Group, neither approach was entirely satisfying, first because the videos weren't always as engaging as they might have been, and second because the production work fell on the shoulders of the instructional technology team, making the process far from scalable.

Although those practices still exist at Babson to some degree, in the last couple of years the institution has also begun using a Web-based service that provides a simple way for faculty--and now students and staff--to create and publish their own videos. As a result use of video has exploded on campus and people are learning what works and doesn't work in making an effective video. Currently, nearly 60 percent of instructors are using video-based slide presentations with audio and other features in at least some of their courses, much of that growth due to the adoption of that new service.

The Hunt for Simplicity

Around fall 2010, the college began looking for a tool that could be distributed to faculty and students for user-generated content. Said Palson, criteria for evaluation focused on two areas: "It had to be accessible via mobile. And it had to be easy to use." Ease of use included the ability for a new user to "jump into it, create something, and it would be ready to go." The instructional technology staff began a pilot using Brainshark and, according to Palson, immediately saw that it was different from what had been used in the past.

One difference is that the video that's produced is hosted by Brainshark in the cloud. So there's no additional upload step required--it's just part of the way the software works. "When users were using this, they were creating their content, hitting save, and they got a URL and they were done," he noted. "That cut the time for users--whether novice or expert--close to half in terms of getting content into the hands of the learners."

On the mobile front, Brainshark uses what Palson calls a "smart player, similar to YouTube." When the URL to the video is shared, no matter what kind of computing device the viewer is on, the player is "smart enough" to detect the type of device and display the content appropriately. The Brainshark mobile video player is based on HTML5.

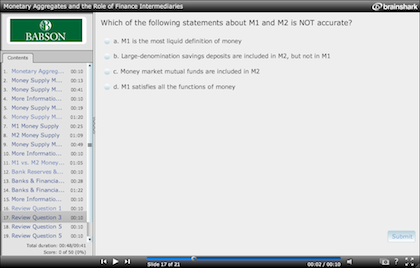

Also, the instructor creating the video can add interactions to his or her presentation, including a sign-in step, poll or quiz questions, other videos, documents for download, and a table of contents. These features are accessible to students on standard computers and those using iOS and Android devices. Users with Blackberry, Windows Phone, Windows Mobile, or webOS devices can view the video presentations, but the interactive features won't work.

| |

Instructors can solicit student responses in Brainshark slides. | |

Based on the success of the pilot, the school obtained an unlimited license to the enterprise edition of Brainshark with a price negotiated based on the size of its population of students, staff, and faculty.

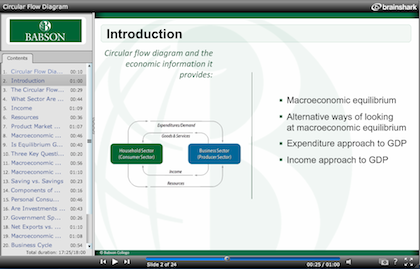

The Sandwich Approach

As faculty members begin integrating other types of media into the video presentations through Brainshark, Babson is coming to a better understanding about what tends to work with learners. Palson called one format that's growing in popularity the "sandwich approach," where short clips of the instructor at the beginning and end are the slices of bread, and the content makes up the filling. As he explained, "We're seeing quite a few faculty creating videos of themselves introducing whatever subject that might be, and then they'll transition that to their content. They might have five or seven slides that are more PowerPoint-like that they'll talk over and maybe animate, and then they might transition into another video, which might be a screencast, showing an Excel document: 'Click in this field and do this.' Then they'll finish that with a video of themselves saying, 'Hope this has helped. Come to my office hours if you need more clarification. You've got this for the extent of the course, so please review it over and over, or download it and take it with you on your smart phone.'"

Each of those various types of content becomes a "slide" in a Brainshark video. The slide structure allows the instructor to mix and match content, which has several advantages, Palson said. In a 15-slide presentation, for example, 10 slides might consist of content "that will stand--to a degree--the test of time. They're key concepts. They might change slightly, but not from year to year." Then the faculty member can update the first few and last few slides to be relevant to a specific class: "During this week online, I read through your posts and Bob brought up a great point on Wednesday about how marketing has changed the face of x, y, and z..."

| |

Many instructional videos produced at Babson use a "sandwhich" approach that places informational slides between videos of an instructor speaking to a camera. | |

That approach, noted Palson, tells the students a few things: "a) My faculty member is really paying attention, even though we're not face to face; b) my contribution is important to the class; and c) this is not just a canned piece of content that they're using over and over." From a student's perspective, he added, "this is great. From a faculty perspective, it's really great as well. They don't have to redo those 10 slides every single semester. They're only doing that for five that are really specific. So it's scalable."

Those slides are maintained in a Brainshark repository accessible by user name and password. That content can also be shared among instructors, Palson said, which is important at Babson since so many courses are team-taught.

Student Use of Video

Some of the faculty members are now using Brainshark in assignments with students. The college has 3,000 students from all over the world studying business and entrepreneurship in traditional, online, and blended formats. For instance, the Fast-track MBA program brings a cohort of students together every four or five weeks for intensive in-person instruction; the remainder of the courses is done online.

For some courses in that program, students are using Brainshark to create and submit presentations, such as "rocket pitches" that describe their ideas for new business ventures or to replace the practice of writing assignments with reports done on video. They simply "submit a link to their faculty members to review and assess them on," Palson said.

Pickup by Other Users

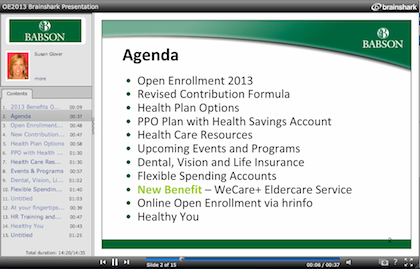

Although Babson began the pilot with the intention of using it primarily for curriculum purposes, members of the instructional technology team would talk up Brainshark with people in other departments. Over the last two years, the service has been picked up by users in human resources, admissions, IT, alumni, and the library.

"Anytime someone was communicating something to the Babson community, that was an opportunity for us to say, 'Take a look at this and see if it would be of use to you. It can easily transform your slides into something that is much more dynamic. You can easily incorporate much more video. You can tell that story in a more dynamic and engaging way than sending a straight email,'" Palson said. HR was an early adopter, using Brainshark to make videos for communicating changes to benefits, for example. As a result, he said, they began getting fewer questions about the changes.

| |

Human resources at Babson has been using Brainshark to communicate with faculty and staff. | |

Now, declared Palson, "Anytime there's any kind of communication going out, which would normally be an email that everyone reads, there's some consideration: Hey, could this be done better with 'a Brainshark?'"

The benefit of the video approach, he added, is that it allows for a "powerful" way of communicating "when you can't get everyone in the room at the same time."

The 'Ultimate' Video

Currently, Brainshark is hosting "thousands" of slides created by Babson faculty, staff, and students. By analyzing the viewing analytics provided by the service, Palson said he and his instructional technology team have come to some conclusions about what makes for effective videos.

First, there is no optimal length of time for a video. In fact, said Palson, "learners are getting more used to watching video online, and because of that, we're actually getting to a point where they'll stay longer."

However, that doesn't mean a 30-minute video will be as well viewed as 10 three-minute segments covering the same material. "That's what we hear from students all the time," he noted. "The first time they might watch it from start to finish, but when they need to go back, they might think, 'OK, I don't need to review one, two, or three, but chapter four is the key thing I need to review the second time.' That's very important."

Second, it's all about the content. "If I give you 10-minute segment where you hit a play button and you watch it for 10 minutes, and you've got somebody speaking about really interesting content and they're doing it in a really interesting way, we're going to see the viewership statistics maintained... If you've got two minutes and it's dry and boring, they'll drop off after 10, 15, 20 seconds. There is a much greater correlation between quality and engaging content and good story-telling than there is to length," maintained Palson.

Short of being an entertaining lecturer, he said, instructors can also use other techniques to engage their audience of students, such as incorporating interactive components, asking a few questions to "keep them on their toes and get some feedback from them in the middle of the presentation."

"If you can piece that all together, you've got the ultimate [video]," Palson said. "But if you can get one of those two, chances are, you've got a really good, engaging piece of content. And some of the statistics, some of the data we've seen through Brainshark has supported that."

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.