Connecting Researchers to the Classroom Virtually

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 07/10/12

|

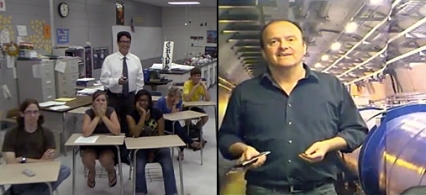

Students at Apalachee High School talk, via video conference, with a researcher at Georgia Tech. Students at Apalachee High School talk, via video conference, with a researcher at Georgia Tech.

|

The 919 faculty at Georgia Institute of Technology are known for their scientific, engineering, and technological prowess. During fiscal year 2011, Georgia Tech, as it's called by the community, won 2,905 research awards, representing a total of $568 million in research funds. A little known program taking place on campus involving just a handful of those faculty members and some fairly standard hardware could provide an effective model for attracting new students into its science, technology, engineering, and math programs.

Direct to Discovery (D2D), as the program is called, began in 2009 to connect Georgia Tech instructors with students in Barrow County Schools classrooms through the use of high-speed networks and high-definition video conferencing. Teachers within the high schools and middle schools develop curriculum in partnership with the higher ed faculty. Then in several sessions throughout the semester, the Georgia Tech researchers use high definition video conferencing in their research environments to "meet" with the students.

How Direct to Discovery Started

The program began about six years ago, when the school system pursued a contract with PeachNet, Georgia’s dedicated, state run, research and education data network. PeachNet connects the bulk of the state’s colleges and universities together with high-speed access to Internet2 -- and just happens to have a backbone connection running through Barrow County. Once that contract was in place, an ambitious former superintendent, Ron Saunders, sought ways of leveraging the Internet capacity with a vision of delivering virtual and blended learning and online assessments, enabling schools to adopt web-based technologies and applications, letting students do Web-based research, and running video for a number of purposes.

D2D officially began when an instructor presented his honors chemistry class at Apalachee High School with an article on carbon nanotubes. Teacher Chad Mote told his students to write down questions about anything they didn't understand, and those questions would be answered by a knowledgeable expert on the topic. In December 2009 Mote connected his class by video to Jud Ready, a member of the faculty at Georgia Tech in the School of Materials Science and Engineering and head of the university's Nanotechnology Lab.

The collaboration continued that semester, including a session in which Ready showed the high schoolers what the nanotubes look like through a scanning electron microscope and culminating in a class wiki in which the high schoolers shared what they'd learned. As Mote wrote in the introduction of that wiki, "These stellar students are putting their brains to work, linking the chemistry that we have been studying in the classroom to 'real science' in a research laboratory."

The partnership continued into 2010. That same year a $234,000 foundation grant allowed both the district and the university to acquire high-definition conferencing gear and provide professional development to the K-12 instructors who would be using the equipment in their classrooms. In fall 2011 the district also received a three-year $1.7 million Race to the Top Funds grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

Within Barrow County, the school system deployed in its data center a LifeSize Bridge 2000 for handling multi-party calls and UVC Video Center 2200 for recording and broadcasting sessions. For two high schools and four middle schools, the district put together 12 mobile collaboration carts with 55-inch LED monitors and LifeSize Team 220 kits containing codecs and high definition cameras and audio gear. It also implemented LifeSize Room and Express setups in eight elementary schools along with collaboration carts that carry a large monitor.

The funding has also allowed the university to acquire videoconferencing gear, including eight LifeSize Team 200 and four Room kits. The Room setups "float" on the campus as faculty members and researchers establish collaborations.

People on both the higher ed and K-12 side, including the students, have also received iPads for the duration of their participation.

The use of high definition gear is vital to the program, explains, Ron Hutchins, Georgia Tech's chief technology officer. Without it, trying to do videoconferencing over the Internet is too frustrating. "You see it cut in and out. The students get so distracted by it that they can't pay attention." The high-definition video and audio streaming enabled by the LifeSize technology "makes it feel like they're more in the presence of the researcher." Plus, he added, "The thing that comes across is the easy nature of the communications. The students feel comfortable asking questions. The professor feels comfortable getting asked questions." There's the sense, he observes, of bringing the professor into the classroom in a way that makes the students feel like they could do the same kind of work.

Developing Science Lessons in Tandem

The D2D program has three components: First, researchers and teachers spend several weeks during the summer working together to develop three to five lessons that will infuse the work of the lab into the classroom curriculum. Those lessons are aligned with state science standards. Second, students use iPads as part of the instruction to create artifacts to demonstrate their learning. That might consist of videos created from still images, original footage, and remixed video from D2D recorded sessions, as well as blogging, wiki entries, essays, and podcasts and vodcasts. Third, the teachers receive targeted professional development to learn how to integrate the iPads into the teaching and learning and to support the development of curriculum with the partner researcher.

The current program is structured to select three science teachers each year who apply to receive a paid fellowship. The idea, according to Barrow's current superintendent, Wanda Creel, is to come up with projects that will take their science teaching to a "different level of learning." For example, she says, when the students talk about nanotechnology, they're able to use Georgia Tech's microscopes and other equipment, "which we would never be able to afford in our classrooms. That's where they're really able to extend their learning."

Those science teachers also agree as part of the fellowship to work with a "partner" teacher at their schools. While the partners don't receive the fellowship, they do receive the iPads and professional training. "So really you end up having six teachers with the experience, as opposed to just the three," Creel explains.

Why Georgia Tech Faculty Sign On

On the higher ed side, according to Hutchins, the faculty members readily agree to participate because they "love" teaching. "They're like little kids in a candy shop with their science, and they love to show it off, [especially] to a group of students in a classroom who get excited and ask them questions."

Hutchins adds that the program also helps participating researchers address stipulations in their grants that call for them to address the "broader impacts" of their science. "What better broader impact is there than education -- especially into the K-12 world?"

So far, the program has attracted nearly two dozen experts in chemical and biomolecular engineering, aerospace, robotics and intelligent machines, physics, and environmental and biological systems, among other disciplines.

The use of the collaboration technology has allowed other faculty within the institution to see possibilities for application in their own classes. For example, Hutchins recounted, one professor realized he could start sending video from the electron microscope he worked with over the network to his students because "he couldn't fit everybody around the tiny screen of the microscope in the lab."

Ancillary benefits are also cropping up within the school district. Now the district is experimenting with delivery of professional development via high definition video, including that summer-time preparation work for D2D; and teachers within the same cohort are connecting with each other across schools through the system to collaborate on planning.

The Attraction of Science in Practice

Ultimately, however, the major benefit of the program may just be how it's drawing students into Georgia Tech.

Barrow County is about an hour from Georgia Tech's location in Atlanta. Sixteen schools serve about 12,000 students. Yet, before the introduction of D2D, for many years no student from that county had attended Georgia Tech. Since the launch of D2D, says Hutchins, five Barrow students have chosen to attend Georgia Tech -- and four of them were women.

Katelyn Roberts, who is pursuing a degree in chemical and biomolecular engineering, was in large part influenced by her participation in the first iteration of D2D at Apalachee High. Now, she makes herself available to visit with students via video to offer a personal view of life at Georgia Tech and to share her experiences as an engineer and a woman in science.

Barrow County, too, is looking to the future. One area of expansion will be to add math alongside the science studies. Notes Creel, the teachers interested in applying for the fellowship positions are "really getting creative. Teams of teachers at the schools are starting to say, 'How can we take science and math teachers together and submit an application and use this for an integrated process?' People are really just trying to find every way they possibly can to bring this technology into the classroom."