Report: Rethinking Developmental Math in Texas CCs

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 06/12/17

An experiment to remap developmental math in four Texas community colleges resulted in a higher pass rate and a larger number of developmental math credits earned by the students who participated. The preliminary results suggested "potential benefits" of the Dana Center Mathematics Pathways (DCMP) approach, which was formerly known as the New Mathways Project.

A recent research brief from the Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness (CAPR) described the program in detail. Most colleges require students to pass a college-level algebra course to earn their degrees. However, according to the brief, most community college students — estimated at between 50 and 70 percent — arrive unprepared to tackle those courses and just a small percentage (20 percent) ever pass them.

In 2012, the Charles A. Dana Center at the University of Texas at Austin introduced DCMP, which reworked the structure, content and pedagogy of developmental and college-level math classes to boost student outcomes. In 2014, CAPR teamed up with the Dana Center to reconsider DCMP. With backing from theUnited States Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences, DCMP worked with four colleges: Brookhaven College and Eastfield College (which are both part of the Dallas County Community College System), and El Paso Community College and Trinity Valley Community College in East Texas. Faculty at each school volunteered to teach the new DCMP courses and received a week of training in the course content and approach.

Unlike traditional developmental math courses, which tend to drill down on "algebraic concepts such as linear equations, exponents and manipulating formulas," according to the brief, the new developmental math course, Foundations of Mathematical Reasoning, emphasizes "development of students' numeracy, statistics and algebraic reasoning skills." The courses use "active learning" environments where students work closely with one another to solve math problems from real life. Rather than tackling formulas and algorithms, students "wrestle with larger mathematical ideas" and take on multistep math problems that are frequently presented in story form or require analysis and comparison of math figures, graphs or tables. One of the goals is to encourage students to persevere through the problems to help them understand that struggle is part of learning. The course materials pull together content from other disciplines, including health and science. Along the way, students also develop their reading and writing skills by working through the word problems and providing written explanations of their solutions.

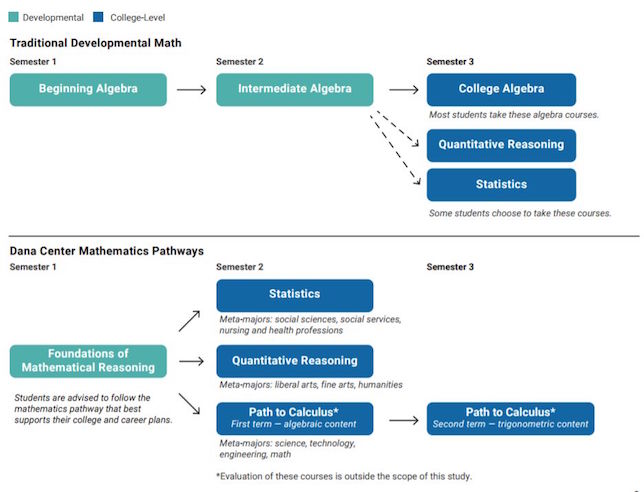

Comparing traditional developmental math with the Dana Center Mathematics Pathways approach.

Students who make it through the first semester of the DCMP foundations course continue in the second semester with another course targeted for their major. It could be quantitative reasoning for those in liberal arts, fine arts and humanities; statistics for those heading into social sciences, social services, nursing and health professions; or "path to calculus" with algebraic content for students who intend to pursue science, technology, engineering or math.

The foundations course was targeted to students who needed one or two developmental math courses and were pursuing humanities and social sciences majors. Those who participated tended to be in their early 20s, more than half were Hispanic, and two-thirds (65 percent) were female. A third (33 percent) told the researchers they had failed a math class in the past.

The findings were "encouraging," the brief reported. Foundations students had "qualitatively different classroom experiences" from the students who attended traditional developmental math classes. And they enrolled and passed their courses at higher rates (47 percent compared to 37 percent). They also earned a larger number of developmental math credits — 1.7 vs. 1.2.

However, the brief noted, one challenge of the project is to make sure students who are eligible for the foundations classes find their way to the new pathways. At most of the colleges, this part of the work involved "painstaking reviews" of major requirements and negotiating with administrators and department chairs. Also, all of the participating institutions needed to build procedures into their advising processes to identify each student's intended major or program of study, with the goal of helping advisers and counselors urge students towards the appropriate math pathways.

Another challenge uncovered in the project involved the transfer of credits. By spring 2016, most of the colleges had succeeded in aligning math requirements for many of the majors with their main transfer college partners, but it continues to be a problem for some schools. At least two of the 11 four-year colleges that were primary transfer partners for the study colleges continued to require college-level algebra courses for math requirements in some non-STEM majors, including nursing and criminal justice. Some advisers, the brief stated, "were therefore hesitant to recommend the DCMP to students in these majors."

A "final report" on the foundations program is expected to be released in 2019. That will include information on how to implement the program, will examine data from a larger sample of students and will examine the longer-term impacts on students' academic outcomes, including their performance in college-level classes.

The report and supplemental tables are available on the MDRC website here.