6 Ways to Build a Better CBE Program

Sinclair Community College's competency-based education program for online students forces candidates to write a "vision" statement, has disabled discussion forums in its courses and boots out students who don't make the 80 percent cut score. And its CBE students are credentialing at three times the rate of students in ordinary online programs.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 08/02/17

While entire colleges and universities have pioneered the concept of competency-based education (CBE) — Western Governors and Southern New Hampshire University's College for America come to mind — others are trying to fit the CBE model into more traditional programs and coming up with innovative ways to mix and match the implementation details.

Take Sinclair Community College, for example. The Dayton, OH-based institution has 30,000 students, with 11,000 registered for online courses. The school's first exposure to CBE came between 2012 and 2016 when the college implemented an "Accelerate IT" program funded by a $12 million Department of Labor Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grant. The CBE format allowed qualified students to start and finish online classes at any time during the college's 16-week semester. Armed with that experience, the school sought to expand its CBE practices into other online courses under the "Sinclair Accelerate" banner.

The goal: to create a CBE program that could reside alongside the college's traditional online offerings. In the first go-around, failure was rampant, according to Christina Amato, the college's competency-based education program manager. As she explained during a session at the OLC Innovate conference, 11 of the school's first 13 CBE students didn't complete their studies successfully. Here's how Amato's institution turned things around.

1) Have CBE Candidates Self-Identify

Initially, the school thought "advanced" students would be the best fit for CBE — "at least to begin with while we were learning," said Amato. But the promise of CBE — flexible starts, the idea of "mastering" competencies before having to move on in lessons, the ability to accelerate studies and finish faster — has broader appeal. Yet, not everybody is right for the CBE format, said Amato. So Sinclair set a goal of helping students figure out for themselves whether they were suitable by putting them through a personal gauntlet.

First, the college has set up a simple screening and intake process. Students need to be able to self-register without any assistance for the CBE courses and declare a program. They need either a 3.0 grade point average for self-registration or no GPA at all but basic developmental placement scores.

"Not having those things will not eliminate them from the program, but they're going to need more assessment and they're going to have to talk to somebody and go through our orientation," Amato noted. "Then we'll figure out if they're a right fit student."

Next, candidates must complete an orientation to the learning management system, D2L's Brightspace — the same stipulation imposed on all online students.

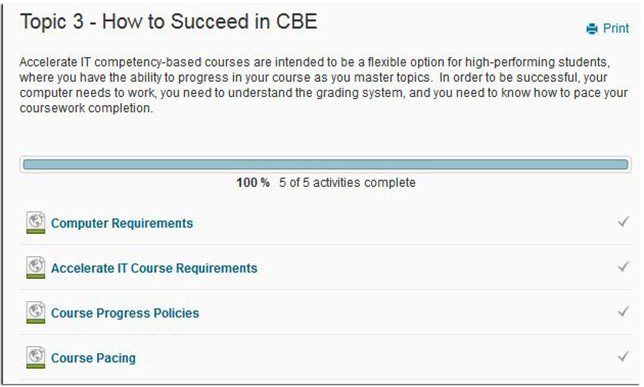

Finally, they need to go through a CBE orientation to learn what they need to know before diving into the program. That orientation "was a work-in-progress for about two years," Amato said. "At first, we threw everything at them, and then figured out we were wasting their time by giving them too much information." The CBE planners backed up and considered just what students really needed to know about a CBE course before they signed on.

Students receive an orientation on competency-based education to help them succeed.

The subject of "success habits," for example, was critical. Candidates needed to understand mastery thresholds. The school set passing scores at 80 percent for all aspects of the CBE program. If a student didn't meet that, he or she would receive two more chances to prove competency. "But they need to understand that it's not a free-for-all where they can keep trying and trying," Amato explained. Once students fail an exam even once, for instance, they need to create a "remediation plan" that lays out how they're going to succeed the next time around.

Another item was an assessment on technology literacy, an obvious requirement for programs covering IT, which students need to pass with the requisite score of 80 percent or higher. Students are also asked to write a vision statement articulating why they're coming into the program. Then they self-assess where they are in their "career spectrum," said Amato. The point is to figure out how big the gap is between where students are in career planning and how quickly they believe they'll achieve their goal. Throughout this process, CBE staff members are watching for signs that "somebody probably needs to have a conversation with this student."

2) Impose Limits on Self-Pacing

The orientation also covers "course pacing." "[Pacing is] really important," Amato said. "We don't allow students to just come in and explore the classroom and hope for the best."

Yet that's exactly how it was handled in the beginning. Students were placed in their courses and told to "go forth and self-pace. It did not work out very well," she observed. "We figured out quickly that we needed to find a way to embed the idea, 'You're responsible for your own pacing. And once you've set a pace, you're accountable for that pace.'"

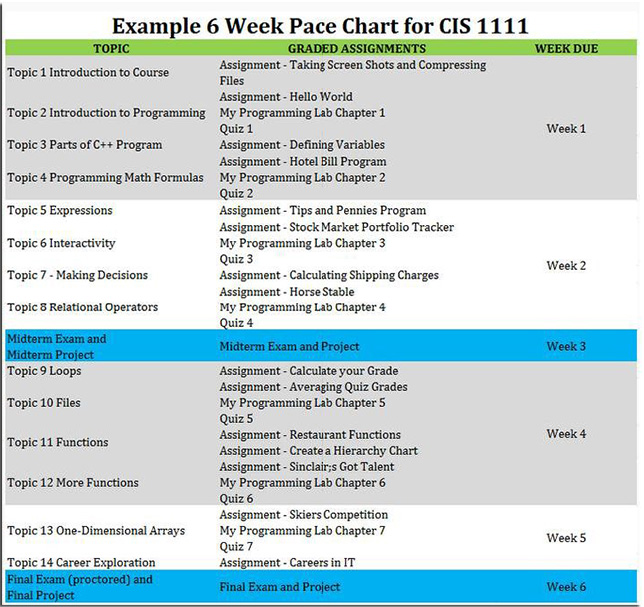

What's that mean? While students can accelerate, they can't fall behind a standard 16-week pace. That's the same length of face-to-face and online semesters. As part of the orientation, students go through sample pace charts and then complete one for themselves.

Sample pace charts help students form realistic expectations of how they will progress through a course.

"We found this was the best exercise to really close the gap between their expectations in the classroom and the reality in the classroom," Amato said. "They can tell us they want to finish a class in four weeks, but when they actually have to plug in the assignments and see how much work they're going to have to do in that period, it's a different conversation. They're able to come out of the orientation with more realistic expectations of what they're going to do."

3) Make It Modular

Sinclair's traditional classes follow a 16-week pattern: 14 topics, one per week, plus midterm and final exams. When the college developed its initial CBE courses, they followed the same pattern. "And nobody accelerated," said Amato. "We found that if you provide them 14 topics, they're going to take 14 weeks, and they're going to do a midterm and a final."

In response, the college "modularized" its CBE classes into "units." Everything is mapped the same as it is in the standard classes, whether on campus or online, but what's different in the CBE version is how the material is delivered and packaged for the student.

As Amato described, students take a pre-assessment at the beginning of each unit. If they pass with an 80 percent or better score, they can skip the unit. If they don't pass, they're required to "drop down" into the unit to tackle the specific areas where they need to do more work. "It allows for acceleration, but it also identifies where students may need a little extra time and help," she said.

That's where the flexibility of the program comes in. Although it's limited to 16 weeks, there may be some units where the student can master the topic quickly and pass the assessments; others may require more time.

Students who fall below 80 percent can finish the course, but they'll be awarded the grade they've earned. When a student can't finish the units in 16 weeks, the college reverts to the same incomplete policy it follows for everybody else: He or she can take an "I" at the end of the term. More importantly, however, in either scenario the student is "converted" to being a regular online student and he or she can't take another CBE course after that.

"We didn't want to create something that was so different for a CBE student, that was like, 'Wow! Why don't we give other students extra time when they don't understand something?'" said Amato.

4) Double Down on Student Support

If that outcome sounds draconian, think again. Sinclair has put in place a dual faculty-mentor and coaching model that has helped to deliver an 80 percent success rate among its CBE students — "which is significantly higher than some of our other classroom success rates," Amato asserted.

The college has long used academic coaching with its online students, according to Amato. It took that model and "built it out to be stronger and a little more robust than it was before." She used the term "case management" to describe the relationship students have with their coaches. Coaches work "one-to-one with students a lot more intensely than they would in our traditional academic advising structure," she noted.

The coach is the individual who monitors the student's progress through the admit phase, which includes the orientation, and stays on top of their momentum through the courses.

Coaches' work is amplified by the faculty, who are less instructors than faculty mentors. It's the faculty member who monitors the student's lab and assessment attempts. If the student fails the first time, he or she discusses the remediation plan with the instructor before trying a second time. And likewise, between the second and third attempts. There are only three attempts.

"If they're stuck, they have to understand why they're stuck and how they're going to get over that and move on in the course," said Amato. The faculty-mentor is the person they have those discussions with.

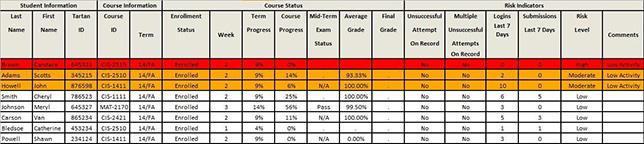

Both roles also monitor weekly LMS reports looking for combinations of factors — low logins, plus low performance, plus other risk factors — that signal possible academic problems. Response is handled collaboratively.

Sinclair's learning management system flags students with potential academic problems.

5) Form Relationships Early and Often

CBE students are either a "direct handoff referral" from the school's internal academic advising unit or they're coming in directly from employers. "We know who they are very early. We're able to have conversations with them during the admit phase," Amato said.

Early on, however, the institution found that it was wasting time "doing things over and over" that students had already gone through. For example, students would talk with an enrollment counselor, providing information about their motivations, their major, their goals, but the information wasn't really captured for later referral. Then they'd go to an academic adviser, "sit down and do it all over again."

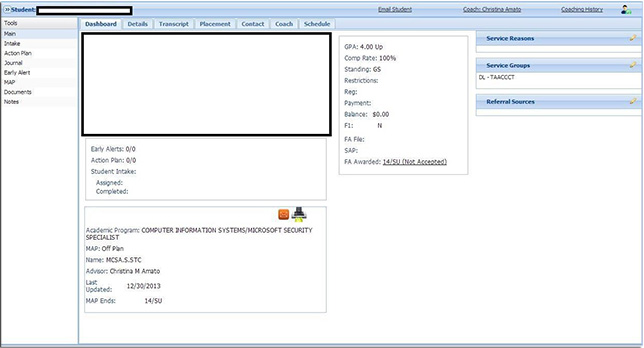

Now, details from those early conversations are recorded and managed through a case management tool, Student Success Plan, which Sinclair developed in-house and has made available to other schools as an open source application. A student's academic adviser accesses SSP's reporting before a first meeting, which makes that initial conversation more meaningful.

Sinclair's case management tool tracks the relationships between advisers and students.

Those talks cover "what we'd expect from the student-coach relationship," said Amato: "You must communicate with me when I reach out to you. You must respond to my e-mails and my phone calls. In exchange, you can expect that I'll be available to you as a coach, and when you have questions, I will troubleshoot for you and I will find an answer for you."

Bonding early is important, she added, because the CBE students "need that really strong, early foundation." Once the student has begun class, it's "very hard to get in touch with them and build that relationship. We're spending more time with them doing it in the beginning." The point, she added, is to build "relationship capital up front that will get them to engage with you later when they're struggling and maybe don't want to."

6) Collect the Data and Use It

Sinclair is energetic about continual improvement. In fact, a lesser institution might have considered calling it quits after that first go-around when almost nobody finished the CBE program on time. But, as Amato relayed, "We would not have graduated out of that first term if we hadn't really extensively collected data and said, 'What happened? What did we do wrong? And how do we improve this?'"

It's something to keep in mind, she added. "If you don't collect the data, then you won't be able to assess and improve." And improve the program did: Now eight in 10 CBE participants make it through their designated programs — a rate three times higher than the standard online program.