5 Quick Tips for Improving Your Instructional Design

Moving a course from brick-and-mortar to online requires rethinking how you deliver content, replicate in-class interactions and pinpoint areas for improvement.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 07/10/19

When you're converting a traditional face-to-face course to online, while a lot of the content may remain the same, the way it's delivered and learned will, understandably, undergo change. A "mastery series" from the Online Learning Consortium (OLC), focused on instructional design, teaches the fundamentals of course design for effective online learning. Recently, longtime instructional designer Elisabeth Stucklen, one of the facilitators for the course, shared five areas to pay attention to as classes are being shifted to an online mode.

1) Start with Outcomes in Mind

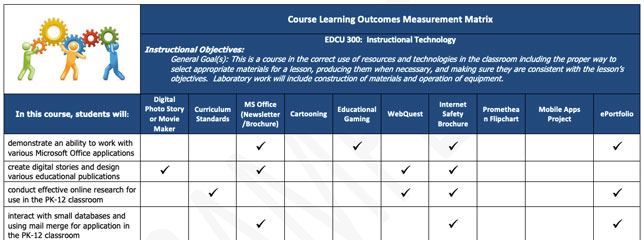

Don't underestimate the value of pre-planning, said Stucklen. It begins by developing a course outcomes matrix, a list of "well-written" learning objectives that express what you want students to achieve by the end of the course, the strategies you're going to use to address them and how you're going to measure whether they've been learned or not.

Sample course learning outcomes matrix (Image courtesy of OLC)

A course outcomes matrix applies to both online courses and those delivered in person. The difference, said Stucklen, is the modality: "There might be different ways to go about achieving those outcomes." As an example, she noted, "In a face-to-face course there's obviously room for discussions. You're there with everyone, you can present content, you can do group activities. But if you go online, you have to do activities in different ways to implement those interactions."

2) Get Personable with Discussion Forums

While Stucklen uses the phrase "death by discussion," the discussion forum has been a standby for online courses for years. Forums still do "have their place," she acknowledged, "but you have to design them well."

The problem that surfaces too often, she said, is that online instructors feel compelled to use the forums with "factual, straightforward information" that doesn't lend itself well to discussion. "What are you going to add when somebody has already come up with the right answer?"

Her advice is to use multimedia tools such as VoiceThread or Flipgrid to shift away from text-based responses and give students formats for mimicking "that face-to-face aspect" and making the experience "more personable."

VoiceThread

VoiceThread allows the instructor to post slides and for students to respond with their own commentary done via webcam, audio or text, which can also be commented on.

Flipgrid is similar "but a little more simplistic," in that it's video-based. Stucklen has primarily seen that tool used for course introductions, where students record themselves with a webcam or smartphone, telling a little about themselves and what they hope to get out of the course.

Either one, she said, "helps to put a face with the name and make it feel like you're not there by yourself talking to a computer."

For her own instruction, she's also considering the use of Kaizena, an add-in for Google Docs. This tool allows users to highlight text, add video feedback, and include links to saved lessons or "explainer" videos that need to be referenced over and over again. Students get access to the same commenting tools as instructors and can reply to comments with their own responses.

3) Reconfigure Your Instructional Strategies

Learning strategies come in two primary flavors: instructor-centered (a demonstration students need to watch or a tutorial they're working through) and student-centered (such as simulations they're performing). Both have their places in online courses, but what's important is to make sure whatever you use is tightly linked to specific objectives in that course matrix you've developed. Otherwise, your coverage will generate "superfluous information," Stucklen said. (And even the superfluous is acceptable, as long as you've signaled to students that it's "additional content," something that's worth studying "later on" but that "isn't really going to help you achieve what we're trying to do in this particular course.")

Case studies fall into the student-centered category as a strategy that helps learners gain and apply real-world understanding. For example, in the master class itself, participants are asked how they'd respond to a situation in which they're acting as instructional designers working with faculty members to develop courses, and as part of that, they need to help the instructors define the course objectives. "Well, how do I work with the faculty on developing these objectives? Is there any information I can give them?" Stucklen suggested. "There is no right or wrong answer. There are just different approaches on how to do it."

In the face-to-face version of the course, that could be a report that's written or an in-class discussion. In an online version, instructors might post the scenario at the beginning of the week and give students time to consider their responses and post videos discussing their answers. By having students weigh in on the various solutions offered, the strategy incorporates "cooperative" or collaborative learning too, allowing "everyone to have the opportunity to learn from everyone else and become both the student and the instructor."

4) Formalize Quality Assurance

When a new online course is created, every aspect of the mechanics needs to be tested — it's important to verify that the links work and go to web pages that still exist and that the content uses file formats, colors and fonts that are accessible.

The use of a quality assurance tool specifically for online classes, such as the OLC Quality Scorecard or the Quality Matters rubrics, will lay out specific and comprehensive criteria to help you evaluate how well you've addressed the fundamentals.

The key point about using these tools, however, is to make sure you get people "from the outside" to rate your course. That includes somebody "who can concentrate on the instructional design aspects" and then two additional people: one "who knows the content" and the other who doesn't. That third person will act as a proxy for the student. After all, Stucklen pointed out, "Students are going to be coming in not really knowing this information. Will what you have in the course make sense for them and will they get what they need in order to achieve the end goal?"

5) Recognize that the Work is Never Done

Continuous improvement is a watchword for online courses. Stucklen recommended two sources for knowing how to prioritize improvements: end-of-course surveys and data.

While end-of-course surveys should include questions on how students would rate their experience with the instructor and the various activities undertaken during class, they also need to include this "basic" question: Do you have any suggestions for improving the course? "We have had people write complete novels inside those surveys," Stucklen said. What they tell you about their experiences can provide a parade of ideas "for improving course components."

The beauty of an online class too is that it generates reams of data that can be useful in figuring out what needs to be reconsidered. But that's also a burden, since it's hard to figure out where to start the analysis. Stucklen uses the student feedback to hone in on the data that will be most useful. As an example, the learning management system will, no doubt, have analytics tools that provide details about "how long students spent in a particular area, whether or not they completed parts of the core service, if they skipped over certain readings and how they performed on exams, projects [or] discussions." The use of an LMS add-in such as IntelliBoard, she added, can be useful "to make it easier to create custom reports."

Stucklen also makes a point of encouraging post-class conversations with the course instructors or facilitators themselves. "They have the unique perspective of being in there and working with the students, and they get to see firsthand where people are struggling" and where the course might need more work.

As a newbie approaching the job of teaching an online course, it's never enough, Stucklen said, to "put information online and figure we're good to go." As you move to the online realm, your job is to shift from "teaching to facilitating." If that concept doesn't make sense, then it's time to find someone to work with "who has the knowledge to help transform that content into an online format that will be effective for the learner and for the facilitator as well."