Penn State Project Finds VR Better for Second Language Learning

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 02/28/19

While virtual reality has proven useful in helping people explore physical realms they can't visit, a study undertaken by a team of researchers at Penn State has found that it can also speed up second language learning among adults, as if they were immersed in the place where that language was natively spoken. An experiment undertaken by scholars in the university's departments of Psychology and Geography used an environment in which the participant viewed the setting through a VR headset and interacted with objects using hand-held controllers.

Sixty-four undergraduates who spoke only English were set up to learn the same 60 words in Mandarin Chinese: Thirty of them were related to kitchen items (plate, sink and table) and 30 were tied to zoo animals (monkey, panda and tiger). The immersive VR approach was used for one of the sets, while the other set employed word-word paired association, in which the English word was paired with the Mandarin word. In three 20-minute learning sessions, students either learned the zoo words in VR and kitchen terms in word-word or vice versa. The order was switched among groups of students. (All were given training on the digital tools used in the project.)

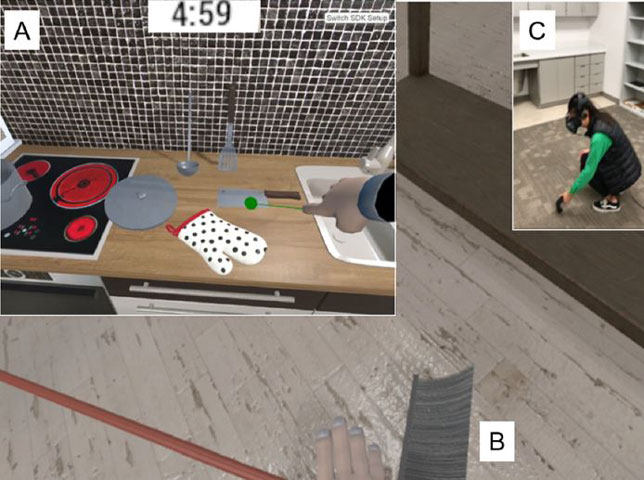

In the kitchen interaction, students used a handset to point to any item and hear the corresponding Chinese word. A timer indicated how much time was left in that lesson.

The words themselves were recorded by a native Mandarin Chinese speaker in a sound booth and were selected as a "representative sample" of what a second language learner might come across in his or her studies.

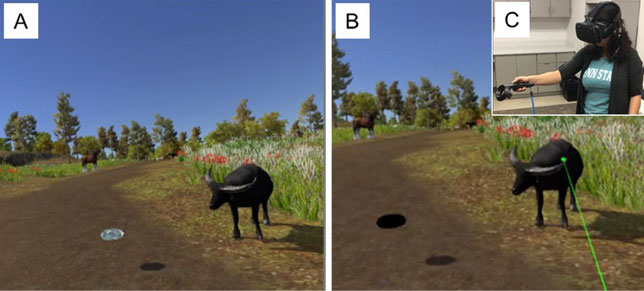

In a timed experience, the students doing the VR portion of the test could use the right handset to laser point to any animal or object and hear the corresponding Chinese word. They could also move through both environments. In the case of the zoo, they could teleport to another location; for the kitchen, they could pick up and move objects.

In the VR zoo interaction, students used a handset to click on animals to hear the Chinese words for them. A "floating gem" would change color to designate that they'd already heard the word for a given animal, but they could click as frequently as they wanted during the time allotted.

After each lesson the students took tests, in which they'd either hear a Chinese word and be instructed to click on the English word (in the word-word version of the test) or point to the 3D picture (in the VR version). Participants got immediate feedback on their performance; a green rectangle would appear around their selection if they were correct, and a red rectangle showed up if they were incorrect. Participants also viewed their overall accuracy percentage score at the end of each testing session.

These two environments were chosen for specific reasons. As a report on the experiment explained, the zoo offered a high degree of interaction and spatial navigation, while the kitchen gave the "highest" degree of interaction and only a moderate amount of spatial navigation, both aspects affecting learning accuracy.

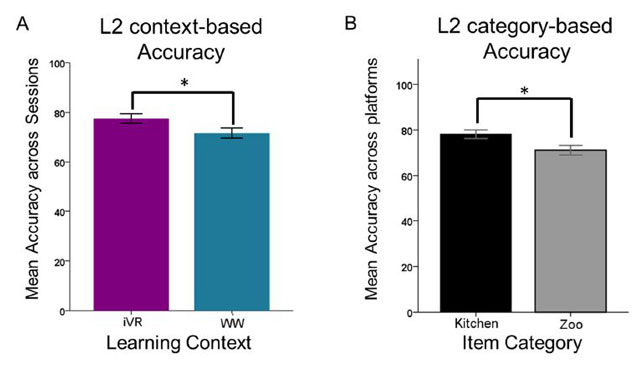

For example, the items learned in the kitchen session were more accurately recognized compared to the items in the zoo session. Also, students were "significantly" more accurate after taking their VR test than the word-word version.

The accuracy of VR for learning was greater than that for word-word testing (A); and kitchen items were more often identified correctly than zoo items (B).

The differences of VR training over word-word training were especially apparent in those students classified as "low-accuracy learners." People who were classified as "highest" performing did equally well in both forms of training, which "perhaps [reflects] a natural predisposition and aptitude towards [second language] learning in these individuals," the researchers wrote. Also, they noted, nearly all of the participants said that the level of engagement was "much higher" in the VR context than it was for the word-word approach.

More research is needed, the report offered, to understand the longer-term impact of VR on language learning and to understand other aspects of the process, such as grammar and morphology.

The entire paper is openly available on MDPI, a publisher of open access journals.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.